The right-wing strategy of pretending that religious conservatives are the real victims—specifically, that Christians are the identity group experiencing discrimination akin to racism or colonialism—reached new lows of unintended irony last year, in a hot take at the conservative journal First Things. Written two days after the 2020 election, the author lamented that some Democrats have suggested abolishing the Electoral College, which would surely empower America’s godless coasts and cities to persecute the religious heartland. As he imagined this coming persecution of the Midwest, our correspondent’s thoughts returned, Proust-like, to the distant memory of a visit to Africa in 1981, where he was swindled by a corrupt Ghanaian clerk with a “gigantic…toothy grin.”

The moral of this blatantly racialized reminiscence? Just as European colonialism systematically destroyed African wealth and development, if “coastal elites” have their way the “new colonialism” will be perpetrated not in Africa, but in America’s heartland. Without the Electoral College and other checks and balances, “Kansas, Alabama, and Tennessee” will become the new “Dark Continent.” Smug, progressive urbanites will forcibly civilize the backward Christian “natives” of Indiana. (This self-pitying vision ignores that the Electoral College was established in part to give disproportionate influence to slaveholding states, and that people of color continue to be oppressed and disenfranchised in the U.S.)

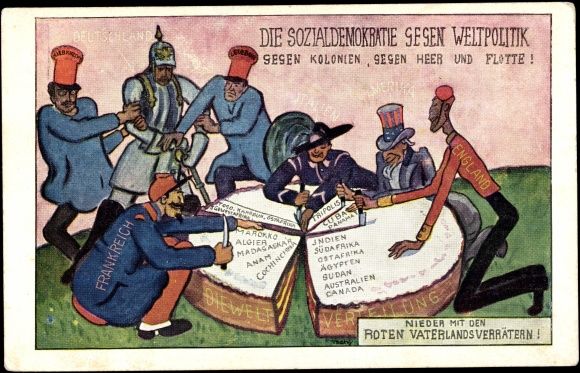

While this martyrology may be an especially confused example of the genre, the rhetorical strategy it represents—identifying Christians in the West with the victims of imperialism elsewhere—is by no means new or unique. In fact, conservative culture warriors have a long pedigree of co-opting and weaponizing anticolonial language. Often, as in the case above, this rhetoric has little to do with genuine respect or concern for those who have endured actual colonization abroad, but is merely a cudgel for beating the “cultural imperialism” of secular enemies at home.

In recent years, religious conservatives’ selective embrace of anticolonial discourse has become especially common in debates about human sexuality. Within Christian denominations based in the U.S., the question of whether to admit and ordain LGBT people has increasingly pushed conservatives into a rhetorical alliance of convenience with conservative African clerics. In 2006, for example, following the Episcopal Church’s ordination of a gay bishop, a number of American Episcopalians broke away from the global Anglican Communion to join a Nigerian branch of the denomination.

More recently, in February 2019, when the United Methodist Church narrowly voted to preserve the Book of Discipline’s commitment to “monogamous, heterosexual marriage,” U.S. traditionalists would likely have been outnumbered without the support of conservative Methodist delegates from Africa. Evangelical culture warriors crowed: here was proof positive that conservatives cared more about marginal voices, while progressives were the true racists. Progressives were “patronizing,” “hypocritical racis[ts],” and “ideological colonial[ists]” who would force their sexual liberation onto benighted Africans.

Other denominations have confronted similar standoffs, pitting the “younger” churches of the Global South against their more sexually liberal parent-churches. These confrontations allow social conservatives in the West to align themselves with African voices and flirt with the normally-anathema concepts of anticolonial theory—a rare pleasure indeed for the right.

At first glance, this rhetorical strategy seems baldly cynical: just one more way the contemporary right has learned to selectively exploit the politics of identity. After all, Christian conservatives do not object to “cultural imperialism” in Africa when it’s their own sexual values being imposed. And when oppressed and marginalized people demand that their perspectives be heard, evangelical leaders regularly condemn them as “cultural Marxists.” Indeed, it seems the only time “authentic” African voices are valuable to conservative evangelicals is when those voices condemn homosexuality or abortion.

However, as much as this rhetorical strategy appears to be just another example of the identity politics of the contemporary right, linking religious traditionalism to anticolonial resistance has historical roots that run far deeper.

Fighting Secularism with Anticolonialism

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, some of the most outspoken critics of European imperialism were in fact religious conservatives. Some of the first Europeans to rhetorically align themselves with colonized subjects did so because they felt alienated and anxious about the creeping secularization of their own societies. Primarily, these early culture warriors worried that their empires were no longer exporting “Christian civilization” to their empires, but rather Europe’s newly-hegemonic secularism.

In the 1920s and 30s, writers who were shocked by the apocalyptic violence of the Great War began to predict the “decline of the west.” Meanwhile, Protestant theologians and leaders in Germany and Britain started to view imperialism itself as a sign of Europe’s secularism, and abruptly transformed themselves into anticolonialists. Given the apparent decay of European civilization, imperialist power no longer seemed an ally in the Christianization of the world, but a liability. For these Christian prophets of European decline, the only way to rescue Africa and other mission fields from the contagion of European secularism was to decolonize them—to cut them loose.

In the years after World War II, Protestant historian Arnold Toynbee’s pessimistic diagnosis—that all civilizations rise and fall, and that European civilization had reached its twilight—exercised enormous influence on a whole generation of Third World and Islamist leaders, offering encouragement to anticolonial movements. Some of the first thinkers to “provincialize Europe,” in other words, were Europeans themselves, conservative cultural critics who felt marginalized by secular modernity and who predicted a European apocalypse. Their disenchantment with European civilization offered useful concepts to anticolonial thinkers and leaders, for whom European decline was a “cause for optimism,” not despair.

Even as far back as the nineteenth century, in the first flush of Europe’s industrial dominance and scramble for African territories, some religious conservatives had already aligned themselves with colonial victims abroad, as a way of attacking their secular enemies at home. In 1840s France, in the context of a culture war about the rights of Catholic educators, the prominent Catholic journalist Louis Veuillot pulled colonial Algeria into the debate, positioning himself as an admirer of Muslim resistance there. God would not bless France’s colonization efforts, Veuillot predicted, as long as the irreligious French refused to support Catholicism and missionary work. Veuillot claimed to sympathize with Algeria’s Muslims: at least they were people of faith!

Léon Bloy’s Rage Against Colonialism

No nineteenth-century religious culture warrior developed a more violent critique of imperialism, or more insistently linked the evils of empire to Europe’s lack of religion, than the caustic Catholic writer Léon Bloy. Bloy was an idiosyncratic figure, combining reactionary Catholicism with an avant-garde aesthetic and a finely-tuned persecution complex. He lived a life of poverty, convinced that a “conspiracy of silence” had denied his works the buzz they deserved. Bloy, a Catholic convert, was influenced by the increasingly embattled and apocalyptic tone of late-nineteenth-century French Catholicism, during a time of Prussian defeat and France’s expulsion of religious congregations from schools.

Ironically, Bloy first developed his criticisms of modern imperialism as part of a quixotic campaign to beatify Christopher Columbus. For Bloy, Columbus had been a true missionary, one of the last emissaries of a vanishing Christian civilization. Beatifying Columbus would be the perfect provocation to throw in the face of the unbelieving nineteenth century. But despite Bloy’s bizarre motives, his writings on Columbus contain some of the most violent denunciations of modern colonization available in nineteenth-century France.

According to Bloy’s sanitized portrait of Columbus, the Christ-like explorer had only wanted to save souls and to protect the New World from political or economic exploitation. Spain’s King Ferdinand, by contrast, was the “ancestor…of the mercenary kings of the nineteenth century.” Ferdinand betrayed Columbus, handing the explorer’s “spiritual children” over to “horrible scoundrels.” Columbus had asked that only true Christians be permitted to set foot in the New World. Instead, Bloy spat, “prisons and galleys were emptied for him. Crooks, perjurers, forgers, thieves, pimps, and assassins were charged with carrying the example of Christian virtues to the Indies.”

Bloy ridiculed the racial and civilizational hypocrisy of these colonizers: “the unfortunate Indians” were only “too happy to be enslaved and massacred by such a superior race.” Bloy even seemed to anticipate modern anticolonial theorists who would “provincialize” Europe and value cultural difference. Instead of leaving the New World to the influence of Christ alone, Bloy wrote, “[Spain and Europe] wanted to digest [the New World] like prey and to spread themselves out” until there was nothing “but Europe throughout the whole earth.”

Needless to say, Bloy’s effort to beatify Columbus ended in failure. But his rage against imperialism had an interesting afterlife. In 1903, Bloy expanded his condemnation of colonialism for the cover editorial of the anarchist weekly l’Assiette au Beurre, a French magazine of satirical illustrations.

In an essay that he would later republish under the title “Jesus Christ in the Colonies,” Bloy mercilessly scorned the cheerleaders of empire—the mediocre journalists, academicians, and government functionaries ready to justify any colonial crime at a moment’s notice. These shameless men (not unlike our own present-day “defense intellectuals”) vouched for “the irreproachable beauty of our colonial institutions, the lily-white innocence…of our officials, and the joy of natives of every color [at being] subjected to the Republic’s tutelary domination.”

Into this sarcastic condemnation of France’s civilizing pretense, Bloy then inserted several recycled paragraphs from his earlier work on Columbus and the godless Spanish colonists. But then Bloy made the connection with his own age explicit. Spain’s exterminatory policies were merely the “dawn” of modern colonial methods: “nothing has changed in four centuries.” Prefiguring later anticolonial theorists, Bloy argued that colonialism tends to brutalize (and justify the brutality of) the colonizers themselves. The most mild-mannered, bourgeois Frenchman who at home would be too squeamish to “[butcher] the lowliest pig,” once in the colonies and invested with arbitrary power was transformed into a torturer and murderer. Any atrocity was justified, because the colonized victims only amount to “a few stink bugs [punaises].”

While Bloy shared some of these talking points with other late nineteenth-century anticolonialists, he filtered them through a uniquely mystical and vengeful brand of Christianity. Bloy viewed all suffering as redemptive and yearned for a final apocalypse that would reward the pains and reverse the fortunes of this life: eternal torment for the hypocritical rich, and eternal bliss for all who had suffered. Because the colonies were the closest thing to hell on earth, it was there that Christ was most present, just as he descended to hell to release the captives after his crucifixion. It was there that Christ still “bleeds for the wretched [les misérables].” Going even further than some socialist and anarchist critiques of empire, Bloy appears to privilege the suffering of the colonized even above that of the working class at home in France.

Like today’s right-wing appropriators of anticolonial rhetoric, Bloy’s acid attacks on European imperialism suggest that he was motivated more by his hatred of smug “secular” elites at home than by genuine empathy for imperialism’s victims abroad—much less their right to self-determination. Nevertheless, his felt sense of alienation at the heart of the empire did give him a vantage point to accurately diagnose that empire’s evils.

The Afterlife of Conservative Anticolonialism

Bloy’s writings had an interesting afterlife in one of the seminal anticolonial statements of the twentieth century, Discourse on Colonialism, published in the wake of World War II by the black Martinican poet and playwright Aimé Césaire. In this groundbreaking essay, Césaire famously portrayed the Colonizer as someone who, for the sake of his own sense of superiority and good conscience, erases any evidence of the humanity and civilization of the Colonized. Like his fellow Martinican Frantz Fanon a few years later, Césaire revised Marxism to decenter the European working class and reclaim a central revolutionary role for the colonized peoples of the world.

In the Discourse’s most memorable gambit, Césaire compared colonialism to Nazism, a nineteenth-century racist prefiguration of Adolf Hitler. In a colonial spin on Arendt’s “banality of evil” thesis, Césaire argued that Nazism was not exceptional, but rather the all-too-predictable blowback of crimes and massacres committed day in and day out in Europe’s colonies. Colonization had “decivilized” and “brutalized” the colonizers themselves and their metropolitan cheerleaders. Césaire then denounced a series of respected European scholars, colonial officials, ethnographers, and journalists for their racism and advocacy of colonial violence, every one of whom had helped make Nazism both thinkable and practicable.

Notably, the Catholic Léon Bloy is one of only a few European writers to earn grudging approval from Césaire. At least Bloy, unlike the hypocritical civilizers, had become “innocently… indignant over the fact that swindlers, perjurers, forgers, thieves, and procurers were given the responsibility of ‘bringing to the Indies the example of Christian virtues.’” The quotation from Bloy’s writings on Spanish colonization is only a passing one. Césaire seems to use Bloy (erroneously) as an example of naïveté: a well-meaning critic of colonialism who did not yet realize how the “bourgeois’ clear conscience” skillfully “filters” out evidence of its crimes.

But in fact, the similarities between Bloy and Césaire extend beyond this brief quotation. Both Bloy and Césaire railed against the complacent hypocrisy of colonialist ideologues and described how colonizers dehumanize their victims (“a few stinkbugs”) in order to absolve themselves. Both argued that older, explicitly Christian justifications for empire were at least more chivalrous than the racism of the secular “civilizing mission.” And both claimed to be prophetic voices crying out for those who would otherwise “have no voice.”

Both even used the specific motif of Martinique’s volcano, Mont Pelée, which erupted in 1902, destroying the Caribbean island’s capital city. In his 1903 essay “Jesus Christ in the Colonies,” Bloy interpreted this recent eruption as a sign of God’s displeasure with the French empire—a divine voice (like his own) protesting on behalf of colonialism’s voiceless victims, a volcanic demand for justice and vengeance. Writing a generation later (and with greater claim to the title, as a Martinican himself), Césaire similarly identified himself with Martinique’s volcano. Césaire’s most famous poem, the lengthy, surrealist Notebook of a Return to the Native Land, recounts his education and feelings of alienation in Europe, his discovery of his African identity, and his poetic calling to speak for all who are colonized and oppressed. Césaire describes the ironic contrast between Martinique’s volcanic powers, on the one hand, and the disappointing, religion-and-rum-induced submissiveness of the island’s “mute” people, on the other. Like Bloy, Césaire assures his countrymen that he “will be the mouth…[and] voice” of their suffering, he will be their volcano, their divinely appointed avenger.

In noting these parallels, I am not suggesting that black anticolonial thinkers like Césaire somehow needed to “learn” anticolonialism from disaffected Europeans like Bloy. Nothing could be further from the truth. Césaire seized rhetorical weapons wherever he could find them, and creatively repurposed them for an arsenal all his own. But the point remains: Léon Bloy’s reactionary Catholic disdain for imperialism’s “civilizing mission,” no matter how cynical and curmudgeonly, proved generative and long-lived. An attack on colonialism which began as a misguided defense of Columbus was quoted approvingly by a man who, with good reason, despised Columbus.

In other words, even a stopped clock—in this case, a religious reactionary invested in his own imaginary victimization—can be right sometimes. After all, there is a kernel of truth to the conservative religious critique of imperialism and colonialism. European colonizers did often justify their violence by maligning the religious or gender norms of those they colonized. And today, international pressure to promote gay rights and other liberal social causes in Africa coexists with broader structures of neocolonial exploitation: forcible Western trade, indebtedness, and austerity measures.

Make no mistake, right-wing culture warriors who cynically pose as inheritors of anticolonialism are not genuinely interested in repairing neocolonial abuses, nor in ensuring real political self-determination in the Global South. But for progressive Christians interested in political liberation, Bloy and Césaire both provide some lessons. Despite his self-pity and festering bitterness toward cultural elites, Bloy reminds us that rage against injustice and the conviction that “the last shall be first” are essential features of radical Christianity.

But mere outrage can quickly turn reactionary when it resists the self-emancipation of the oppressed. As Césaire teaches us, no culture, no religion, no political program can flourish without “the right to initiative”: that for the formerly colonized, “no doctrine is worthwhile unless rethought by us, rethought for us, converted to us.” Yes, people of faith in post-colonies should be allowed to follow their own authentic path—not disciplined into Western molds or conscripted into Western culture wars. But a culture can only choose its future freely, as Césaire says elsewhere, “when the society in which it finds expression is free.”

Joseph Peterson is an assistant professor of history at the University of Southern Mississippi, specializing in modern France, empire, and religion. A portion of this essay was adapted from a presentation at the French Historical Studies conference in 2019.