Those wielding power in the U.S. have long been cruel, and cruelest especially to those most vulnerable among us. Instead of celebrating and embracing these vulnerable people and communities, our country has consistently criminalized them, frequently using their precarity as leverage to steal, to coerce, and to suppress. Rather than welcoming the migrants among us, for example, we collectively outlaw them, using their migrant status to steal their labor while depriving them of (the paltry) legal protections of citizenship and self-determination. Those in power leverage their criminalized migrant status to pirate child and elder care work, food work, and construction labor while gorging themselves on the proceeds.

The same might be said for my classmate who, though she was only a child, had not had an abortion, but simply suffered from epilepsy—and how she suffered for it. By virtue of her sex (and her disability), she was ostracized, treated by her peers in our strict Catholic grade school as an outsider, marked and separated by some mystical force. What must one do, I remember wondering at the time, to recover? Would she need to perform some act of contrition, penance, or “good works?” While I’ve since learned how these systems of power operate, how they at once use and exclude, the fundamental question remains an important one. What will those in power increasingly require of women, queer, and especially in the wake of the Texas anti-trans law, trans persons? What extra service and acts of contrition will they demand?

The specter of a post-Roe world, one heavily structured by medical and childcare costs as well as the hyper-surveillance of sexuality and instruction in schools, would leave women and gender nonconforming folks with uteruses in states of increasing precarity. This precarity is indeed “deeply rooted in the Nation’s history and traditions,” to borrow Samuel Alito’s language from the leaked draft ruling overturning Roe, one that created a gendered gap in opportunities still reflected in salaries for women, who earn 82 percent of their male peers (63 percent for Black women). Before Roe, that number was 57 percent. Over the last five decades, women have made enormous strides against workplace and wage discrimination in part due to the Court’s interpretation of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Overturning Roe, which relies on that very same reasoning, threatens turn back the clock on these civil rights while increasing the vulnerability of those forced to carry pregnancies to term in a country that gouges its residents for essential medical treatment and childcare. It threatens, in short, their right to survive.

Women, across racial and ethnic groups, but especially in ways determined by race and class, have historically been tied to this commodification of vulnerability in the U.S. We have, historically and collectively, demanded that they remain in unwaged household work or in the artificially devalued domestic labor market. That has been especially true for Black women, who were long forced by the practices and prejudices of white supremacist society into domestic work as cooks, maids, washerwomen, and sex workers. They made the most of their communities from the Deep South to the North and Midwest under Jim Crow and fought hard for basic rights, higher wages, better opportunities, and safe working conditions. Yet far too many Black women, bound by the constraints of racist laws and practices, found few options apart from bodily service to the racist patriarchy.

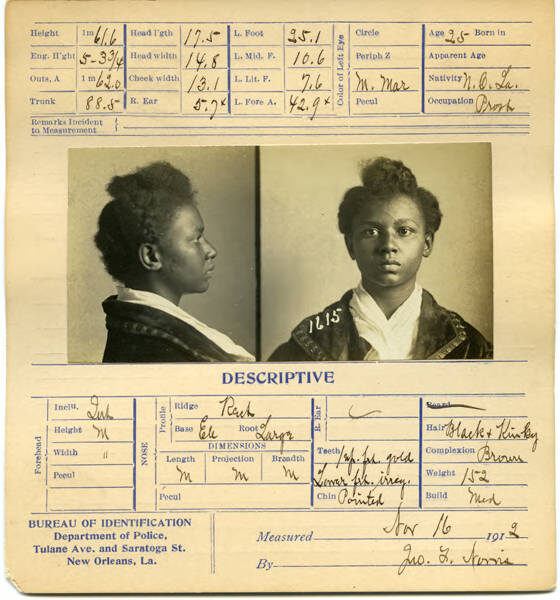

What options were available to Clara Williams, a Black sex worker arrested for allegedly stealing thirty dollars from her client? She might have found piece-work as a washerwoman in New Orleans, yet that work had already begun to evaporate with the commercial washing machine. What recourse would she have had if Gus Holmes, the “guileless fellow” she slept with, simply refused to pay—if he was in fact the one doing the stealing? Would the police, who didn’t charge Holmes for any crime, have even cared? Racism and misogyny worked in tandem to keep young women like Williams—perhaps still only a child judging by her photo—in a state of hyper-vulnerability, one that made them easy prey to those with more wealth and power.

We might ask the same questions on behalf of white women. What might they have done in a world truly open to their ideas and abilities? What might Gladys Delmar, arrested for being a “suspicious person” and charged with “operating a disorderly house within five miles of a military camp,” have chosen for herself if given the chance? Perhaps she found sex work lucrative or exciting. Or maybe she viewed it as the only way she could make ends meet. What if she considered the work her patriotic duty, a way to serve the war effort? Whatever the case, should we blame her for trying to survive in a deeply patriarchal, hierarchical, and oppressive society?

And what of the women incarcerated as “insane” after being discarded by their husbands? Was “Mrs. John Morehiser born Mary Grady,” an Irish immigrant who “became jealous” after being abandoned by her husband, guilty of any great crime? What about her answers to the incessant questions of the white male doctor, Yves LeMonnier, made them inadequate, “not always rational?” Was Dr. LeMonnier annoyed that “her answers [we]re slow to come,” that he had to ask “several times before being answered?” Did this pause, this hesitation after losing so much, warrant incarceration in the State Insane Asylum?

While “Mrs. John Morehiser born Mary Grady,” Gladys Delmar, and Clara Williams had vastly different experiences with the authorities, the world available to them was overwhelmingly shaped by racist, sexist, and capitalist expediency. Elite white men preyed on despair, and created systems to maximize its production. From gendered exclusions to the explicitly carceral capitalism of sharecropping, the predator class squeezed profit from precarity. In the aftermath of slavery, they understood this first principle of racial capitalism as a primary vehicle for their own wealth and power. It is one lesson they have not forgotten despite the erasure of slavery and its afterlives from public memory.

Although women share bonds of exclusion, as Angela Davis explained, “it is possible for white women—especially those associated with the capitalist or middle classes—to achieve their own particular goals without securing any ostensible progress for their racially oppressed and working-class sisters.” Historically, that has meant a women’s suffrage movement, for example, that was deeply invested in lynching as a way to elevate white women’s enfranchisement. Thus we have Rebecca Felton Latimer, a celebrated suffragist and the first woman to serve (for a day) in the U.S. Senate, famously trumpet that “if it needs lynching to protect woman’s dearest possession from the ravening human beasts—then I say lynch, a thousand times a week if necessary.”

Likewise, the white supremacist women of the United Daughters of the Confederacy leveraged their power as mothers—a status they denied Black women in ways similar to today’s anti-“CRT” “mothers”—to embed Confederate propaganda in schoolbooks and erect monuments to slavery and white supremacy on street corners. The racist propaganda campaign they helped wage supported the passage of new voting rights restrictions, upheld by the Supreme Court in Williams v. Mississippi, and the rise of lynching as an instrument of racial terrorism. The legacy of their efforts continue to shape our lives today.

We are seeing the fruits of just such a movement today, one that seeks to restrict voting rights, to suppress classroom critiques of white supremacy, and to restrain forms of sex and gender that challenge rigid hierarchies. It is no accident that the Court gutted the Voting Rights Act in Shelby County v. Holder before broadening its attack on civil rights, of which Roe is one element. Nor is it a coincidence that Republican resistance to abortion rights is actually grounded in its decades-long war to maintain segregated schools. In truth, what we recognize as the Republican turn towards authoritarianism has itself been decades in the making.

I don’t know what a potential world after Roe will bring, but if our collective past is any indication, it is likely that the precarity, uncertainty, and desperation we experience now will only increase as features designed by the predator class. These vampire elites have blocked the passage of childcare funding, safety-net expansion, and rolled back the child tax credit that lifted millions of children out of poverty and improved infants’ brain development. If they cared about children, about families, about basic human decency or the ability to survive, Republicans would have created a world of generous benefits to children, of easy access to resources and opportunities. Instead, they did the opposite, because Republicans don’t really care about infants or their cognitive function, but about expanding their own wealth and power.

I want to close with a passage from Davis’ majestic essay, “Let Us All Rise Together”:

“I want to suggest, as I conclude, that we link our grassroots organizing, our essential involvement in electoral politics, and our involvement as activists in mass struggles to the long-range goal of fundamentally transforming the socioeconomic conditions that generate and persistently nourish the various forms of oppression we suffer. Let us learn from the strategies of our sisters in South Africa and Nicaragua. As Afro-American women, as women of color in general, as progressive women of all racial backgrounds, let us join our sisters—and brothers—across the globe who are attempting to forge a new socialist order—an order which will reestablish socioeconomic priorities so that the quest for monetary profit will never be permitted to take precedence over the real interests of human beings. This is not to say that our problems will magically dissipate with the advent of socialism. Rather, such a social order should provide us with the real opportunity to further extend our struggles, with the assurance that one day we will be able to redefine the basic elements of our oppression as useless refuse of the past.”

May we have the courage to reject this refuse of a past defined by exploitation—one “deeply rooted” in our country’s repugnant “history and traditions”—in solidarity with one another and destroy once and for all the predator class and their torture-for-profit schemes.

William Horne, Co-Founder and Editor of The Activist History Review, is an Arthur J. Ennis Postdoctoral Fellow at Villanova University who writes about the relationship of race to labor, freedom, disability, and capitalism in post-Civil War Louisiana. He is a former high school teacher, barista, and warehouse worker and is an avid home gardener. He holds a PhD in History from The George Washington University and can be followed on Twitter at @wihorne.