The volume around the discourse of modernity is always set to max, and no surprise. For many from the liberal tradition through Marxism, modernity is to be regarded as a singular achievement. Not only did ordinary men and women win political and legal rights for themselves which have shocked Aristotle and Plato. For liberals and Marxists modernity was an awakening from the dark ages of superstition to the Painean “Age of Reason.” As Kant famously put it, through the modern world, humankind emerged from its “self-imposed” immaturity. Marx and Engels went even further. They celebrated the rise of the modern bourgeois epoch. The modern era disposed of “fixed-fast” prejudices so beloved by reactionaries and heralded in a new liberal-capitalist era. This era, they proclaimed, has “wonders far surpassing Egyptian pyramids, Roman aqueducts, and Gothic cathedrals; it has conducted expeditions that put in the shade all former Exoduses of nations and crusades.” Of course, even these would be surpassed by the communist society to come, which would overcome the limitations of bourgeois society and liquidate the ancient regime.

But modernity has never been without its fierce opponents. Note the critiques coming from the political right. In his Considerations on France Catholic arch-reactionary Joseph de Maistre laid the blame for the French Revolution largely on the heads of the philosophes, chastising them for being “unable to replace those foundations ignorantly called superstitions” and characterizing their arguments as “an essentially destructive force.” In his A Defense of One’s Own Life, John Henry Newman lamented the growing atheism of the 19th century and asked “what a prospect does the whole of Europe present at this day.” Today, a movement of “post-liberal” thinkers proposes it is possible to surpass liberal modernity by rolling back its achievements. Such revanchism should be of great concern to all of us.

The political left has launched its own critiques of modernity. Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer believed that the emergence of modern emancipatory politics and the authority of reason risked being flattened into an ideology of instrumentalism and consumerism. In their Dialectic of Enlightenment, they warned that society would fall into fascism if it failed to overcome the modern turn toward these ideologies. More recently, political theorist and cultural analyst Wendy Brown has argued neoliberal rationality appropriates the language of freedom to justify the limitless empowerment of economic elites. The resentment this generates among working class people, she argues, will express itself in attacks against the most vulnerable members of society.

Intellectuals from Frederick Douglass through Charles Mill have pointed out that modernity has always included measures to exclude and exploit racialized minorities. Oftentimes this was justified by appealing to very modern sounding pseudo-scientific doctrines justifying racial eugenics and subordination. Modernity’s “racial contract” has thus straightjacketed its emancipatory potential.

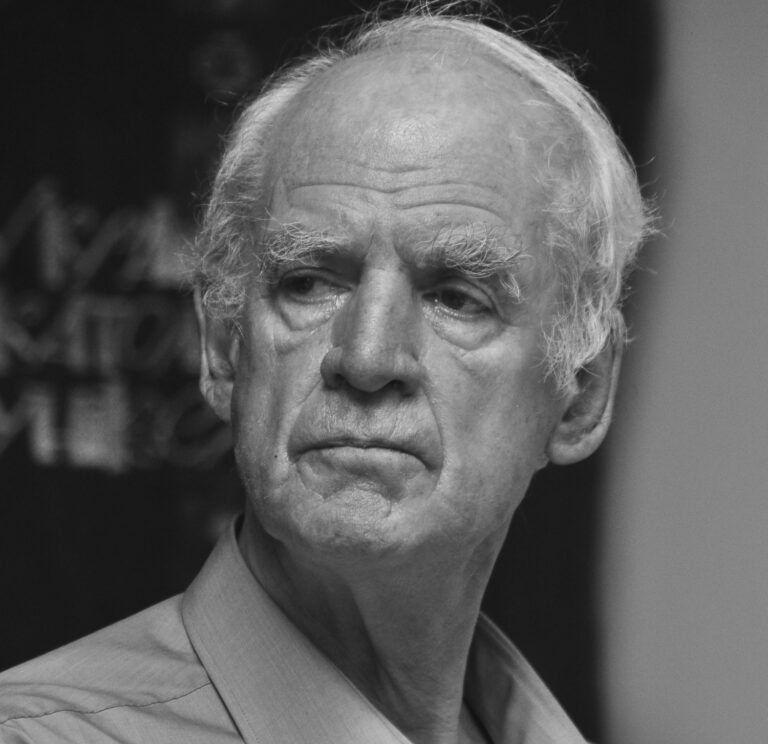

One of the most complex and deep analyses of modernity is that offered by Charles Taylor, a Canadian philosopher and center-left Roman Catholic. Taylor’s work is vast and erudite, defying easy summation. Yet there exists one throughline from Taylor’s early work defending Hegel through his towering magnum opus A Secular Age. Taylor is convinced that while modernity may be a mixed blessing, a blessing it remains. For all that it has brought about – the potential of atomistic alienation, narcissistic self-centeredness, and of course violent reaction – modernity created conditions where all persons can have their worth recognized both as individuals and social beings. It transitioned human societies from hierarchical ideologies to one where all human beings were regarded, at least in principle, as morally equal. I believe this accomplishment has to be defended and, in fact, radicalized through a renewed emphasis on economic justice.

The Origins of Modernity

Stories about the rise of modernity are often reductive. In one telling they focus on a justified triumph of a given principle or way of life; in another they focus on an equally myopic tale of decline and fall; and in another telling modernity is narrated as a roller coaster story of rise and then decline and fall.

Consider Steven Pinker, who boils modernity down to a triumphant tale of Enlightenment and progress, and thinks all our problems can be chalked up to too much irrational extremism on the left and the right. In Suicide of the West the conservative Jonah Goldberg paints an even simpler picture, summarizing modernity in graph after graph chronicling the real and alleged achievements of capitalism. All would be well if only we could wind the clock back to the golden age of Ronald Reagan, Margert Thatcher and hair metal. The decline and fall narrative is even found in vastly more sophisticated takes, like Alasdair MacIntyre’s After Virtue. In his account, MacIntyre details the moral descent from Aristotelian teleology to the vulgarities and violence of emotivism, the conviction that right and wrong are matters of preferential taste, making the choice between murder or non-violence akin to deciding between flavors of ice-cream.

In contrast, Taylor offers a more nuanced account. He is resolutely dialectical in his approach and recognizes that one cannot extricate the triumph of modernity from its underside. They are intimately linked, with each modern advance generating new anxieties and problems which have to be addressed.

Taylor is, in the end, ambivalent about modernity. In Taylor’s account, modernity must be situated within the context of two preceding and historically competitive “premodern” forms of moral life, which he sets out to describe in his 2003 primer Modern Social Imaginaries. In the first form life is shaped by “the Law of the people.” One can hear a conservative connotation implicit in this form, with its determined social hierarchies and rules grounded in tradition and collective identity. But it does not have to have this connotation. Historically, liberal and socialist revolutionaries accused aristocracies and ruling classes of violating the moral economy of the “people.” Law, in other words, demanded a sense of duty to the ruler’s subjects.

For societies shaped by the second type of premodern moral order, cosmology grounded social life, and communities expressed and corresponded to a hierarchy of existence in which they were but one element. For instance, writes Taylor, “the king is in his kingdom as the lion among animals, the eagle among birds, and so on.” Society must “resonate with nature,” and unless it does so, “the very order of things is threatened.” In the heyday of this second form, “hierarchical complementarity” prevailed. Each person stood in the organic order of things and their duties matched their place. Breaking from the cosmological hierarchy in the name of self-interest, individualism, or expression was considered dangerous at best and sinful and unnatural at worst.

The designation of these moral orders as “premodern” shouldn’t be taken as a sign of their disappearance. One of modernity’s defining features has been a nostalgia for the premodern, especially the political and ontological certainty these moral orders provide. Not coincidentally, many contemporary “national conservatives” try to fuse these two forms of life together. This is because in spite of their conceptual incompatibility, national conservatives are attracted to the tantalizing prospect of a transcendent moral order to which all human beings must submit whether they like it or not. They are less concerned with the fact that an order focused on the tribal or national “Law” of a particular people and their traditions cannot be squared with a profoundly universalistic vision of humanity as subject to the same natural laws flowing from a rationally comprehended cosmos.

For Taylor, religion, and Christianity specifically, was the source of modernity’s break from these two presumptions about the modern world. This is of course a profoundly different, even disturbing claim, that bucks the conservative condemnation of liberal modernity as somehow a perverse break with our Christian past. To put it simply, secularization didn’t happen to Christianity but through Christianity.

One break took place in the developments that followed from the Reformation, which focused intellectual and religious attention away from our embeddedness in a transcendent moral order such as God’s “Great Chain of Being” and toward the inner life. Radical reformers like Martin Luther famously criticized the Catholic Church for supposing that the faithful needed an intermediary to connect with God. Theologians and philosophers advocated an inward turn with the intent to cleanse Christianity of its idolatry and bring about an intensification or religious experience.

Originally this focus on individual faith was intended to intensify the connection to one’s religion by stripping it of vain rituals and the association with worldly powers. As late as the 19th century the quintessentially Protestant individualist Soren Kierkegaard wrote Attack on Christendom to chastize the Danish national church for providing a community which made the way to faith easier, when the true task was to make it harder for the individual to ensure their relationship to God was more authentically religious rather than social. But whether these thinkers intended the Reformation’s individualism to energize faith, the kind of liberal individualism Protestantism helped bring into being would have far wider effects. This included the cultural shift to foregrounding individualistic reason alongside individualistic faith, and it was these new forms of Enlightenment rationality which would in turn come to question the most fundamental truths of Christian doctrine.

By treating Christianity as self-secularizing Taylor ironically echoes the very different argument of Friedrich Nietzsche circa The Genealogy of Morals where Neitzsche claimed “…in this way Christianity as a dogma was destroyed by its own morality, in the same way Christianity as morality must now perish to: we stand on the threshold of this event. After Christian truthfulness has drawn one inference after another, it must end by drawing its most striking inference, its inference against itself…” There is a stunning sense then in which, for Nietzsche, secular nihilism can be seen as the final kind of self-punishment Christianity inflicts on us. The yawning pain at the absence of Christianity and God is itself a symptom of having yearned for God for so long, with the feelings of guilt over his death themselves emerging from the long history of Christian morality about the good and personal responsibility.

Of course Taylor and Nietzsche treat the results of Christian self-secularization very differently. For Nietzsche, the Christian roots of liberalism, socialism and democracy are very apparent and require the whole rotten plant be uprooted wholesale. As he put it in The Anti-Christ it is “Christian value judgment which translates every revolution into mere blood and crime! Christianity is a revolt of everything that crawls along the ground directed against that which is elevated: the Gospel of the lowly makes low.” But for Taylor, when we recognize the Christian basis of modernity the most devout can become harmonized to it. We see the progressive movements which emerge today, whether explicitly Christian or not, as carrying on the Gospel’s hopeful message of loving one another and caring for the least among us.

Many of us simply treat secularization as a footnote in the story of modernity, accepting what Taylor calls the “subtractive” thesis that to be modern simply means to no longer believe in what we once believed. Plenty of progressives would actually see this as an improvement, and to the extent secularism has entailed a rejection of authoritarian and hierarchical moral orders in both thought and action it is actually a profound step forward. But not one without complications. This brings us to Taylor’s own complex evaluations of the modern world.

Have We Ever Been Modern?

Taylor disputes the typical narrative that secularism is a one-way path to unbelief or militant atheism. Gods and magic don’t simply disappear, as Weber’s thesis about the profound “desacralization of the world” suggests. Instead, modernity and postmodernity produced a huge number of new belief systems: new age religions, neo-paganism, conservative religious revivalism, cults, militant atheism, populist nationalism and so many more. Some of these systems repudiate the past, others bastardize it, and some attempt to restore it even while being stamped by the modernity they reject. Often these belief systems have an expressly or implicitly religious quality to them, even if they may not all be to the taste of more dogmatic believers.

Taylor dedicates a great deal of time examining one belief system in particular: the Age of Authenticity, or “expressive individualism,” associated with a variety of thinkers and movements from the 19th century onwards that culminated in the counter-cultural movements of the 1960s. Expressive individualism was a Romantic belief that we had to develop or realize our distinct humanity, coupled with a critique of modern society as both alienating and domineering. It assumed both radical and reactionary forms, alongside facilitating the emergence of a huge number of new faith traditions ranging from New Age Spirituality to queer Christianity. Philosophers responded to the “Age of Authenticity” in very different ways. The liberal socialism of J.S Mill was very much on board, stressing the importance of “experiments in living” for all, while fascist thinkers like Martin Heidegger bemoaned the loss of authenticity in a modern world governed by technical reason and mindless chatter. Many of the 1960s radical left movements experimented with new kinds of community and sexualities considered immoral and a threat to Christian values. From Taylor’s standpoint, expressive individualism echoes the sentiment “here I stand, I can do no other” in the face of an intolerant world.

In his 1991 published lecturers The Malaise of Modernity, Taylor offers cautions against optimistic appeals to authenticity. As much as authenticity can push against society’s limits, Taylor also thinks authenticity has been a catalyst for tremendous narcissism and social detachment. Movements for authenticity can themselves quickly become ideological and even authoritarian. In his classic book The Jargon of Authenticity Adorno offers a scathing account of how Heidegger’s seemingly profound criticisms of modernity actually replicate its most authoritarian elements. Heidegger’s account of authenticity, says Adorno, amounts to submitting one’s individuality to a project of national revival which requires the coldest resolve to condemn faux-humanist compassion.

I’d like to push Taylor’s and Adorno’s observations further. If we conceive modern liberal societies as radically fallen and reject all forms of moral value and historical analysis as sentiment, authenticity can be mobilized into demands for a politics that draws legitimacy purely from political will. The Nazis often justified their authoritarianism on populist lines, claiming that any and all restrictions on the Party and the Fuhrer were constraints on his expressing and directing the national will. Heidegger himself made this very conflation in the 1930s, when he insisted on the centrality of Germany as a uniquely authentic and spiritual nation destined to overcome the decadent and nihilistic metaphysics of the liberal capitalist West and the communist East (along with their Jewish backers). This is a politics that becomes indifferent or even pathologically attracted to the power of inflicting suffering on others.

But the Age of Authenticity also had moments of profound self-reflection and emancipation. This was often the case with religious movements which broke from typical faith traditions without falling into nihilism and atheism. Instead they attempted to construct new kinds of faith that held a deeper resonance for believers—what Galen Watts calls the “religion of the heart.” Take, for instance, the oft-mocked “spiritual but not religious” designation. Many conservatives blanch at those who identify this way. But Watts points out that many who identify as spiritual take their faith very seriously—sometimes more so than religious traditionalists. They are on a quest to find or create a faith tradition which draws heavily on what has come before but speaks to their deepest eschatological yearnings in the present. Watts observes that as a consequence of this individualistic approach, many professed “spiritual but not religious” practitioners actually claim their faith means a great deal to them.

Moreover Taylor criticizes reactionaries who disparage these new kinds of religiosity for corroding respect for tradition and political authority. Taylor can thus be viewed in contrast to an intellectual like Yoram Hazony who insists that one should perform belief even if one lacks faith for the sake of maintaining a venerable tradition. A modern emphasis on authenticity draws attention to how profoundly “fake belief” pollutes a spiritual experience. There is nothing more damaging to a religion like Christianity than billions playing at a faith that once compelled genuine reverence because it would be politically expedient. This would be less religion and more a simulacra or even mockery of the real deal.

The Limits of Taylor’s Analysis of Neoliberal Capitalism

Taylor’s argument about how the Age of Authenticity constitutes one response to modernity is tightly reasoned, though I think he misses an important danger foregrounded by figures like Fredric Jameson and Slavoj Zizek. This is how the rationalizing basis of modernity has often led to the conceit of assuming that we moderns are less tempted by the allures of ideology than our predecessors. The benefit of Taylor’s approach to modernity is its charity, its critical but appreciative take on the developments of the modern world. But what it lacks is an acknowledgement that some of modernity’s developments are far more the products of systems of oppression and ideological blinkerdness. This brings me to the fundamental limitations of Taylor’s account of modernity.

In his Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism Jameson suggests that a tremendous turn of attraction toward ideologies is rooted in a loss of “futurity,” the belief that history is genuinely possible and so there is an alternative to the status quo. Bogged down in the competitive and atomistic forces of capitalism, it can be difficult for people to believe that an individual or social movement can transform things for the better. Nihilistically resigned, hope is lost. The result has been a shift in our experience of existential purpose. We turn away from the future and look toward the traditions of the past, which are endlessly mined as the sole, but decaying, reservoirs of meaning. Sometimes this is done in the most crass way imaginable, turning what were once sacred values into cheap and partisan kinds of self help, a la PragerU videos saying you should believe in God because of the health and social benefits. The ultra-Mammonesque prosperity gospel offers a similar response promising that belief brings wealth and social status at no cost but a small monthly payment to the preacher. It’s hard to imagine a thousand atheists causing as much damage as when a faith of the soul looks so keen to sell its own.

Another response within the nostalgic tendencies has been to combine the competitive and hierarchical ethos of neoliberalism with a renewed emphasis on stratification by ethnic identity, religious chauvinism, and even race. Those on the alt-right who endorse a kind of “cultural” or “white” Christianity and evoke Christian and Crusader themes to mobilize whites against “invading” migrants and non-Christians are a clear example. As Zizek points out, these identities are often treated as objects analogous to religious idols, invested with an irrational power and significance that nullifies critical thought and moral responsibility. This “identitarianism” comes with a longing for power in the face of neoliberal hegemony.

It is difficult to account for these trends and provide a sufficient political alternative within Taylor’s framework. In the end, what is needed is a materialist analysis. One of the great weaknesses in Taylor’s account of modernity has been a curious wariness and indifference to questions of political economy. Even Taylor repeatedly acknowledges that his position is vulnerable to accusations of “idealism” from a materialist standpoint, but surprisingly his response has simply been to emphasize that ideas matter along with material conditions. He has rightly chastised vulgar Marxism for its economic reductionism. This is true enough, but going to the opposite extreme is no better. There is no doubt that the moral and religious dimensions of modernity foregrounded in his work are exceptionally important, but any account of the modern world that sidelines the power of capitalism is missing a huge part of the story.

Not coincidentally one consequence of Taylor failing to take material conditions seriously enough can be seen in the admirable but limited nature of his political proposals. Beyond recommending a familiar mix of social democratic reforms, most of his recent work has focused on the need to secure “recognition” for marginalized communities by the liberal state, which includes affirming their fundamental rights and privileges under the law.

Though these reforms are to be applauded, we need a much more ambitious agenda today. All progressive liberals and socialists should reject the idea that there is no alternative to the world we live in, or that if there is an alternative it lies in resuscitating the hierarchical societies of the past. Historical faith doesn’t mean being optimistic or naive, but willing for ourselves that most demanding of feelings: hope. And especially hope for the least among us. We need a renewed emphasis on securing economic wellbeing for the least among us first and foremost; we need to limit the growing influence of capital on our increasingly strained democratic institutions; we need to reinvigorate the labor movement as part of a long term aspiration to build workplace democracy. More than just bandage solutions, these structural overhauls would help to shift power toward the demos for the first time in forty years and serve as a jumping off point for potentially more ambitious projects. Above all they would help restore hope that a real alternative to the hegemony of neoliberalism is possible, and that modernity needn’t be defined by the triumph of Mammon.

Matt McManus is a Lecturer at the University of Michigan and the author of The Political Right and Equality (Routledge) amongst other books.

Photo Credit: Makhanets