A procession of white American Christian tourists walked toward us, making their way along a winding trail in the open-air archaeological museum, the “Nazareth Village.” The Museum was built during the 1990s on a historic hillside in Nazareth that the Nazareth Trust claims was “untouched since New Testament times.” It opened its doors in 2000, with the hope of “showing the world what Nazareth was like in the time of Jesus.” Along the trail, they inspected sheds with tools that first-century carpenters like Joseph or Jesus might have used. Dressed in the attire of first-century peasant boys, my Nazarene friends and I were part of the spectacle. We kicked a ball around, surrounded by rocks and a few donkeys. One American tourist looked into my eyes with a gaze of unsettling fascination.

Today I know what the eyes of many American tourists, especially white Anglo-Saxon Protestant tourists, see and unsee. They do not see me, only through me, to what I represent to them. Stripped of my historical existence, I was dressed in the garbs of a biblical fantasy. I was not in my Nazareth, but in theirs.

This spectacle was not out of the ordinary. European Christians and their descendants have made pilgrimages to holy sites in my native land since the Crusades. These pilgrimages took on a new form in the nineteenth century. Coinciding with the biblical literalist movement, Western Christians traveled to Palestine hoping to restore the “land of the Bible” as they knew it in the text. In the art, maps, and travelogs they produced, Christian pilgrimages unburied remnants of the first century, while burying the real Palestine—a world of native peasants and workers, bustling markets and busy streets, literature and art, as if we were a profane aberration that must be hidden away for a mightier, more sacred vision.

Today, hundreds of thousands of Christian tourists visit Nazareth and other holy places in historic Palestine every year. They participate in tourist projects that enable foreign Christians to see the Nazareth they want to see: an ahistorical, frozen-in-time landscape from the first century. The “Holy Land” is valued for its land, but not for its people. Nazareth, like the rest of Palestine, is rendered in these Christian tourist operations as a “land without a people” that can be taken, occupied, and “restored” by outsiders. This is the entire premise of the Zionist project, as well.

Zionism itself is a settler colonial project born from nineteenth-century European ethno-nationalism, which posits Palestine—a historic homeland with a religiously diverse population—as the exclusive homeland of the Jewish people. I was once speaking to a local Palestinian Christian vendor in Bethlehem who told me, “There is no such thing as Christian Zionism. There are only Zionist Christians.” Indeed, Christian Zionism is not about Christianity per se. It is a political movement that uses Christian theology to support and lobby for a Jewish supremacist settler colonial state in Palestine and the dispossession, dispersion, and subjugation of its non-Jewish native population.

The Settler Colonial Roots of American Christian Zionism and the Palestinian Nakba

At the helm of the nineteenth-century British Empire, Anglo-Protestant Christian revivalists wove together apocalyptic theological beliefs with their country’s expansionist ambitions. They espoused literal interpretations of prophetic biblical texts, such as Daniel and Revelation, and perceived Jews as a separate nation within God’s divine plan, destined for restoration to Palestine. This event, thought the restorationists, would trigger Christ’s second coming and the end-time battle prophesied to take place on the hills of Megiddo in Palestine, known as Armageddon.

In his book Christian Zionism: Road-map to Armageddon?, Stephen Sizer illustrates how this eschatology was notably sharpened by the theologian John Nelson Darby’s “dispensational premillennialism.” Darby is often recognized as the “father of dispensationalism,” the belief that Jews have their own distinct dispensation and are not required to convert to Christianity before being restored to Palestine—in contrast to “covenantal premillennialism,” which holds that Jews must convert first. Darby’s extensive travels to North America, coupled with his active participation in Bible schools and prophecy conferences, played a crucial role in spreading dispensational premillennialism throughout the continent. His theological development found fertile ground in North America, as his legacy was further propagated by Cyrus Scofield and Dwight L. Moody, who discovered in Darby’s teachings a foundation for their own fundamentalist movement.1

Darby’s millennialist theology did not take root in the United States in a vacuum. Rather, it intertwined with and adapted to the prevailing Anglo-American settler culture and the burgeoning colonial ambitions of a nation looking beyond its borders. This theology fed on American national myths, shaped by the doctrines of Manifest Destiny that drove Anglo-Protestant settlers across the centuries to expand their conquest westward, believing it their providential right to do so.

This millennialist theology took on a global horizon after what Frederick Jackson Turner called “the end of the frontier.” The American settler colony began to extend beyond the continent as it strove to become an empire. Emboldened by a blend of eschatological and nationalistic fervor, a number of Americans embarked on pilgrimages to Palestine, some even attempting to establish settlements. These included the early efforts of the first U.S. Consul to Jerusalem, Warder Cresson, who attempted to build a proto-Zionist settlement near Jerusalem. In 1866, Mormon leader George Adams established a Protestant colony outside the city walls of Jaffa, and in 1881, the Spafford family founded the famous American Colony north of the Old City of Jerusalem. All of these were material manifestations of a millennialist, colonialist drive to prepare the Holy Land for the fulfillment of biblical prophecy.

These projects largely ended in failure. Documented extensively in his book American Palestine: Melville, Twain, and the Holy Land Mania, Hilton Obenzinger writes that, despite the secondary role of the United States in the imperial endeavors in Palestine, “the most important effect of actual contact with the Holy Land was the more concrete construction of the imagined bond between the mythic destinies of America and Palestine for use in settler-colonial nationalism in both lands.” Thus, these efforts were part of a broader American preoccupation with appropriating Palestine into the American settler narratives which elide the indigenous inhabitants of both Turtle Island and Palestine.

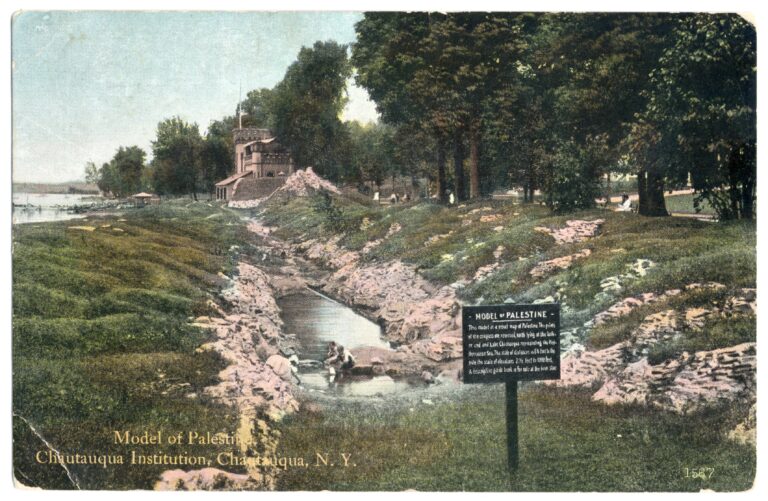

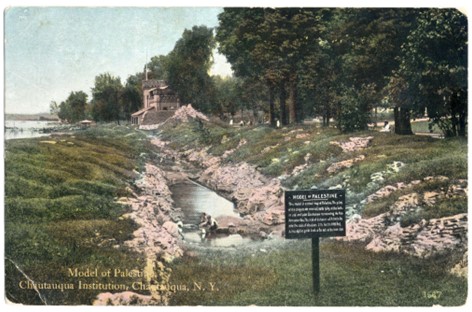

Through literature, art, and even constructed landscapes like the Palestine Park at the Chautauqua Institute in upstate New York,2 Americans reimagined Palestine not as it was, but as they wished it to be—a land without a people for a people without a land, thus setting the stage for Zionist endeavors and contributing to the erasure of Palestinian presence and history.

Christian Zionists made Palestine an image to revive their colonial zeal. British imperial policy made the image into a reality. These theological perspectives were not limited to religious circles but also shaped the worldviews of high-ranking officials and decision-makers in imperial and military spheres. A notable example is Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury, a fervent advocate of Zionism and a key figure in the Christian Zionist movement in London. It was actually Ashley who coined the phrase “a country without a nation for a nation without a country,” which became the slogan of the Zionist movement five decades later. He was also the chairman of the British-established Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF). Founded in 1865, it collaborated with American military engineers and scholars to conduct a comprehensive archeological and topographical survey of Palestine.

The PEF played a pivotal role in bolstering restorationist claims to the land. As Salman Abu Sitta put it, the maps produced by PEF engineers and scholars were the “blueprint for the Nakba.” The maps produced from this survey emphasized biblical locations and narratives on the one hand while hiding the existence of over 2000 Palestinian towns and cities on the other. These maps were part of a plethora of scientific and scholarly literature as well as a body of art and photography, which solidified the invisibility of Palestinians in the Western gaze. The maps also served a military function—aiding the British conquest of Palestine in 1918. In addition, they continue to justify the displacement of Palestinians and the ongoing efforts to ethnically cleanse Palestinian territories, particularly in Jerusalem.

Thus while British and American scholars saw Palestine as a sacred territory tied to end times, the product of their scholarship was translated into a political project that upended the world that Palestinians knew. 530 villages filled with life, stories, folklore, and literature—made unseen in maps—were eradicated by Zionist militias in the 1948 Nakba, the century-long experience of exodus rendered non-history, silenced by the blowing trumpets of Jewish “return.”

These imperialistic biblical prophecies were self-fulfilling, as key British imperial decision-makers breathed life into them, transforming them into colonial policy. Foreign Minister Arthur Balfour, an anti-Jewish white nationalist, was himself a Christian Zionist. The 1917 “Balfour Declaration” delivered to Lord Rothschild committed the colonial British Mandate to give the land of Palestine to the Zionist movement, without any consultation from the people of Palestine themselves. The document recognized the political claims of the “Jewish people” to Palestine; meanwhile Palestinians, 95% of whom were non-Jews at the time, were referred to as “existing non-Jewish communities.” This document inaugurated the 100-year history of Palestinian invisibility, dispossession, and rightlessness which continues to this day.

The Real/Palestinian Nazareth

A few years ago, while I was a Master’s student at the University of Chicago’s Divinity School, I walked into the Howard Goodman Memorial Room where my class was about to be held. On the wall was an old map, dating back to the late 1880s, which depicted “Palestine”—a barren territory, marked with over 100 sites from the Bible but with not a single of the 2000 Palestinian villages, towns, and cities that existed when the map was made. There was no indication that this was a map of “biblical” Palestine; it pronounced the reality of Palestine now and forever. It was a ‘map without a people.’ More than 500 of those localities would be uprooted later in 1948, but well before then, they were already erased by this map and countless others like it. While Nazareth was there, it was the biblical Nazareth meant to be seen, not the real Nazareth where I grew up.

Today, Nazareth is the biggest Arab city under the rule of the state of “Israel,” and home to many Muslim and Christian families, including my own. During the 1948 Nakba, Zionist militias invaded Arab villages around Nazareth. This premeditated campaign of ethnic cleansing through brute military force displaced 800,000 Palestinians from their homes and homeland. Few places escaped this displacement, including my hometown. Since it was left standing, Nazareth transformed into a massive refugee camp for Palestinians who were violently uprooted from surrounding villages like Saffuriya, the birthplace of Mary, and Ma’alul where the only remaining structures are two churches completely surrounded by an Israeli military camp.

The fascination with the Holy Land in the nineteenth century took an intriguing turn in Nazareth, a pivotal yet underrepresented locale in the biblical narrative. Thus, the boyhood of Jesus of Nazareth became a canvas for speculative fan fiction by the pilgrims, who overlaid their own imaginations onto this significant chapter of Jesus’ life. Such was the extent of this imaginative engagement that Mark Twain who, upon his visit to Nazareth as depicted in Innocents Abroad, felt compelled to craft a parody, observing that the city “has an air about it of being precisely as Jesus left it.”3 Twain’s Jesus is comical, mischievous, and constantly subverting authority, but like other fictions of Jesus’ boyhood at the time, he reflected white American middle-class boyhood. This is still the American Nazareth, not the Nazareth of my boyhood.

This interest in Nazareth lies so deep in the American imagination that it even emerges in the contemporary rap scene. Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright” draws a poignant comparison between Nazareth and Compton, both impoverished and oppressed cities, with Jesus imagined as a Black child growing up in a ghetto or, as the title of another song of his suggests, a “good kid” in a “m.A.A.d. city.”

Kendrick Lamar’s image of an oppressed and struggling city might be closer to the real image of present-day Nazareth. Israel built a major Jewish settlement on the hills it seized from Nazareth in 1948 and named it Upper Nazareth. This much wealthier and well-developed settler Nazareth effectively hinders the Palestinian Nazareth from growing or expanding its territory. Despite being a vibrant hub of economic, cultural activity, and a focal point for political resistance, recent decades have seen the city increasingly besieged by poverty and gang violence, a situation maintained by a police force that is active only in repressing our protests and demonstrations.

~ ~ ~

When Nathanael asked, “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?,” Philip replied, “Come and see.” (John 1:46)

Living in the US, I introduce myself as “Amir of Nazareth.” Yes, I am making a tongue-in-cheek reference to Jesus, but I am also making another political point. There is a real Nazareth, with real people living in it, and their story is that of every Palestinian village, city, and refugee camp. American Christians have to open their eyes and lend their ears to hear the stories of the people of this land.

My Nazareth is the Nazareth of Jesus, yes, but it is also the Nazareth of Tawfiq Zayad, a prominent Palestinian communist poet and political leader who rallied his people during the 1976 Land Day revolt, when Palestinians from all across Galilee united together and, despite facing violent repression, successfully resisted the dispossession of their lands. During the demonstrations, Israeli forces opened fire, killing six Palestinian young men and injuring many others. Through their unity and sacrifice, thousands of acres of Palestinian farmlands in the Galilee were saved from expropriation.

In Zayad’s poetry I find the spirit of resistance, resilience, and resurrection we know in Christ, and to which we appeal in times like these as we witness our people in Gaza resist an evil and depraved war of genocide: “They hung us, an entire nation, on the cross/ They hung us on it/ So… /We would repent” Zayad carries on, “This setback is not/ The end of the world…/ Nor are we slaves/ So wipe your tears /Bury the dead/ And rise again[.]”

The story of Nazareth is that of Gaza and the rest of the people of Palestine. Palestinians are people who against all odds have survived a relentless force in history that has been trying to wipe them from existence. Erasure and dispossession, exodus and crucifixion, have defined their experience for the last century, since Zionism, backed by the Western empires, dominated their lands and lives. They have been punished continuously for choosing to resist their erasure, and for this they pay unimaginable sacrifices. Despite all these sacrifices, Palestinians continue to fight for truth, justice and liberation.

The bloody war of genocide on our people in Gaza is ongoing with no end in sight. These are apocalyptic times. “Apocalyptic” also means revelatory. Witness then, and see that Palestinians, as described in Tawfiq Zayyad’s poem, are a “nation on the cross,” enduring suffering and persecution in their struggle to simply exist as a people in their own homeland.

The question remains: will those who profess the Christian faith in the West choose to repent as they witness the crucifixion of our people in Gaza? Will they choose to sever their theological and material ties with Zionism? Will they choose to see beyond the “end of the world” and fight for a new, redeemed world where Palestinians have the right to return to their homeland and live a fully dignified life on it?

Amir Marshi is a Palestinian PhD student in Anthropology and History at the University of Michigan, hailing from the city of Nazareth.

An author note: I would like to extend thanks to Kai Ngu for their encouragement and contribution in helping to get my thoughts on paper. Additionally, I owe a deep debt of gratitude to Kathleen Blackburn, my creative writing instructor at the University of Chicago. Her guidance on earlier versions of this piece was instrumental, and her influence continues to inspire me.

- Scofield helped popularize Darby’s dispensationalism through the publication of the Scofield Reference Bible, a pivotal work that popularized these beliefs among millions of American Chrsitians through its detailed annotations and doctrinal interpretations. For example, in his interpretation of Genesis 12:3—“I will bless those who bless you, and whoever curses you I will curse”—Scofield described God’s promise to Abraham as the fourth dispensation, positing that the Israelites would exclusively inherit the land in a covenantal promise. This is just one example among many. By the end of World War II, his commentary had sold over two million copies, embedding these ideas in millions of American households. ↩︎

- Palestine Park featured a scale model of cities like Jerusalem and Bethlehem, hills such as Mount Zion and the Mount of Olives, and the Jordan River, serving as visual evidence of this imagined Holy Land for those who were not able to travel there. ↩︎

- (537, quoted in Obinzinger, 199) ↩︎