Frederick Douglass denounced American Christianity in no uncertain terms. “I can see no reason, but the most deceitful one,” Douglass thundered at the end of his first autobiography, “for calling the religion of this land Christianity” (85). Outraged by the immorality and brutality of enslaving that discredited the devotion of enslavers, Douglass argued that they were fraudulent Christians. He claimed that “the overwhelming mass of professed Christians in America” were too (87). The phrase American Christianity itself was a misnomer, and any true Christian must be the enemy of its perversions.

Douglass’ assertion that the majority of American Christians failed to meet the most basic standards of “the Christianity of Christ” offers not only a damning indictment of the role of slavery in the U.S., but also of contemporary American Christianity. A plurality of white American Christians support Donald Trump, accused of serial sexual assault and misconduct, a fraudster, and racist who has repeatedly defended Confederates and enslavers and sought the support of white nationalists. Trump’s consistent embrace of racist rhetoric and ideas led to an increase in hate crimes among his supporters. His campaign has explicitly courted white evangelicals and extremists, promising a gathering of them in February that “if I get in, you’re going to be using that power at a level that you’ve never used before.” In July, he told a similar group of religious extremists at the Believers Summit that “You won’t have to vote anymore, my beautiful Christians,” while his running mate spoke at a national revival with self-declared “prophet” and Christian nationalist Lance Wallnau. They have repeatedly invoked the “greatness” of America’s past—one defined by slavery, segregation, misogyny, and discrimination—as the centerpiece of their campaign.

What does it mean that so many self-declared Christians today pronounce that “America is a Christian nation” and look with reverence and nostalgia on its allegedly Christian past of slavery, segregation, white supremacy, and genocide with its worship of nativism, misogyny, and mass immiseration? What vision of the faith does it conjure that so many of these Christian nationalists not only celebrate these pasts of oppression, but actually aim to revive them in the present?

Douglass engages a similar set of questions in his autobiography with damning conclusions about the true devotion of American Christianity. His attention to the spectacles of white piety—my term for performances of white public morality—show how easily Christian devotion legitimized systems of exploitation, abuse, and mass death. If indeed America was a Christian nation from slavery through Jim Crow—the span of Douglass’ work—Douglass shows just how detestable making it so “again” would be.

Douglass observed both a deep piety and unapologetically firm commitment to slavery in Edward Covey. Douglass had been rented to Covey by Thomas Auld, Douglass’ enslaver, a practice that not only allowed “poor whites” to reap the benefits of enslaving but also allowed enslavers like Auld additional income during slower times in the agricultural year. Covey grounded his authority and ruthlessness, which earned him a profitable reputation for “breaking young slaves,” in his fanatical Christian devotion. He “was a professor of religion,” Douglass recalled, “a pious soul—a member and class-leader in the Methodist church” who leveraged his sense of the divine in service of slavery (47). He deployed a white supremacist morality that fetishized property and power, which allowed him to operate a torture-for-profit scheme to the glory of God.

Enslavers like Covey used Christianity as a tool of oppression from the earliest days of the colonies. They justified the brutalization and commodification of African-descended people as their Christianizing mission, but quickly altered this principle of colonial laws in the 17th century after enslaved people sued for their freedom on the grounds that they had been baptized and converted to Christianity. In 1667, the Virginia colonial legislature announced that “it is enacted and declared by this grand assembly, and the authority thereof, that the conferring of baptism doth not alter the condition of the person as to his bondage or freedom.” Enslaved people could no longer win their freedom by converting to Christianity. In 1670, they acted again, stipulating “that no negro or Indian though baptised and enjoined their own freedom shall be capable of any such purchase of Christians”; and in 1691 proclaimed “that no negro or mulatto be after the end of this present session of assembly set free by any person or persons whatsoever,” unless their enslaver paid to deport them from the colony. Enslavers wove Christianity into the law to create a framework where they could enslave even their own children (1662), making slavery the bedrock of their “Christian nation” from the very start.

A careful student of the relationship between laws and religion, Douglass observed that American Christianity not only could not relieve the horrors of slavery in the U.S., but that it had in fact played a central role in creating the chronic lawlessness that lay at the heart of enslaver devotion.

Douglass applied his understanding of the white piety of American Christianity, one that he honed as an abolitionist agitator in the years before he published Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, to his own life and experiences. In the opening lines of his account, he explains:

My father was a white man. He was admitted to be such by all I ever heard speak of my parentage. The opinion was also whispered that my master was my father; but of the correctness of this opinion, I know nothing; the means of knowing was withheld from me.

Douglass was separated from his mother by his enslaver while he was still too young to know her and before he could learn his father’s identity. The key to this grotesque practice lay in the relationship between the predatory public morality and laws created by enslavers to their own benefit. “Slaveholders have ordained,” he explained, “and by law established, that the children of slave women shall in all cases follow the condition of their mothers… for by this cunning arrangement, the slaveholder, in cases not a few, sustains to his slaves the double relation of master and father” (13-15, my emphasis). In both law and Douglass’ own eyewitness account of enslavement—there is a very famous example of the practice from one of the Founders—white piety explicitly stipulated an ownership relationship between white parent and Black child, one founded on the morality of unrestrained consumption.

White piety was central to American Christianity. A poor singer, Covey forced Douglass to sing hymns during his family devotionals. “He would read his hymn,” Douglass recalled, “and nod at me to commence.” Covey prayed loudly and consistently so that, “strange as it may seem, few men would at times appear more devotional than he.” The spectacle of Covey’s prayers blended with the public nature of his white supremacist violence as a “n****r-breaker” in a perfect articulation of enslaver devotion. Yet, Douglass concluded, “every thing he possessed in the shape of learning or religion, he made conform to his disposition to deceive.” His self-proclaimed righteousness and morality gave him deniability when the brutality of his crimes came into public view. When Douglass escaped from Covey after being nearly beaten to death, for example, Thomas Auld “ridiculed the idea that there was any danger of Mr. Covey’s killing me, and said that he knew Mr. Covey; that he was a good man.” Auld even told Douglass “he expected that I deserved it” (50, 54).

Like Covey, Thomas Auld was a devoted man. He had “attended a Methodist camp-meeting” revival that “if it had any effect on his character,” Douglass remembered, “it made him more cruel and hateful in all his ways; for I believe him to have been a much worse man after his conversion than before.” In American Christianity, Thomas Auld found a justification for the torture and exploitation he had loved so dearly. He “made the greatest pretensions to piety. His house was the house of prayer. He prayed morning, noon, and night.” While Douglass and his enslaved companions were “nearly perishing with hunger, when food in abundance lay mouldering in the safe and smoke-house, and our pious mistress was aware of the fact… yet that mistress and her husband would kneel every morning, and pray that God would bless them in basket and store.” Although some might critique the forced-deprivation Douglass experienced as a perversion of devotion, Douglass argued that this white piety celebrating expropriation and plunder represented the cornerstone of American Christianity (44-45).

For Douglass, white Americans devoted themselves to property and power, contorting their beliefs not only to fit this fetishization, but to enhance it. “After his conversion,” Douglass explained, Thomas Auld “found religious sanction and support for his slaveholding cruelty.” In one especially gruesome example, Thomas Auld would “tie up a lame young woman, and whip her” until she bled, “and, in justification of the bloody deed, he would quote this passage of Scripture—‘He that knoweth his master’s will, and doeth it not, shall be beaten with many stripes.’” The white piety of Auld, in which “he prayed morning, noon, and night” and made “himself an instrument in the hands of the church in converting many souls,” became in his hands a weapon as literal as the whip (45-46). This brutality was no contradiction for Auld, but central to his understanding of himself as righteous and enslaved people as existing exclusively for the pleasure of his own profit and power.

Covey’s Christianity was just such a tool, perfectly crafted and honed through his projection of white piety to give a respectable veneer to the beating, rape, theft, torture, and brutality of the work of enslaving. He bought an enslaved woman, for example, “as he said, for a breeder,” and used to “fasten up [a married man] with her every night.” The twins she bore as a result, Covey “regarded as being quite an addition to his wealth.” Rather than viewing himself “guilty of compelling his woman slave to commit the sin of adultery,” Douglass found that Covey “deceived himself into the solemn belief, that he was a sincere worshipper of the most high God.” In fact, Covey viewed the product of this coerced sexual relationship as a blessing. Likewise, his use of violence and starvation to “break” enslaved people only led Covey to believe, like enslaver Thomas Auld, that he was “one of the many pious slaveholders who hold slaves for the very charitable purpose of taking care of them (47, 50-51).”

The spiritual innovation of enslavers Covey and Auld transformed the Christian ethics of caring and providing for “the least of these” into a rigid public performance of white religious devotion. They prayed loudly and emotionally, projecting white sincerity while acting as a party to rape, or in the case of Auld, taking a woman severely maimed by slavery as a child and “set[ting] her adrift to take care of herself,” an act that could only have led to her starvation and death. “The Christianity of America is a Christianity,” Douglass concluded, “of whose votaries it may be as truly said, as it was of the ancient scribes and Pharisees,” that their belief is simply a performance, a spectacle used to justify their own power (46-47, 87).

Intrinsic to white piety was the deprivation of human dignity and Christian devotion to enslaved people, codified by the colonial Virginia legislature in the 17th century. Thomas Auld understood this relationship clearly, quoting passages from the Christian Bible as he stripped and brutalized one of the women he enslaved. If American Christianity as Auld understood it granted him humanity and superiority, enslaved people must be kept from accessing it. While that might seem a hypocritical or absurd position for someone charged with “converting many souls” like Auld, it was a central tenet of the white piety of American Christianity. As Douglass explained:

While I lived with my master in St. Michael’s, there was a white young man, a Mr. Wilson, who proposed to keep a Sabbath school for the instruction of such slaves as might be disposed to read the New Testament. We met but three times, when Mr. West and Mr. Fairbanks, both [Methodist] class-leaders, with many others, came upon us with sticks and other missiles, drove us off, and forbade us to meet again. Thus ended our little Sabbath school in the pious town of St. Michael’s. (46)

American Christianity could not liberate or protect those enslaved by its sanction. In fact, American Christianity was premised upon the unthinkability of Black religious practice that might correspond to claims of humanity. The threat of even the possibility of Black piety was so great that the high priests of American Christianity literally attacked Black Christians with clubs to prevent it.

Only what amounted to a massive white conspiracy to promote racialized lawlessness, whitewashed in the waters of white piety, could have made enslavement possible. Douglass emphasizes this dynamic throughout Narrative, most forcefully through the brutal and arbitrary murders of several members of his community. These acts, he observed, made clear that “killing a slave, or any colored person… is not treated as a crime, either by the courts or the community.” In fact, after murdering an enslaved man named Demby for refusing an order, the murdering overseer claimed that it was his duty to kill enslaved people who defied his orders. “He argued,” Douglass recalled, “that if one slave refused to be corrected, and escaped with his life, the other slaves would soon copy the example; the result of which would be, the freedom of the slaves, and the enslavement of the whites.” The whole white community was thus responsible, and indeed, actively involved in meting out violence to guarantee white supremacy. Failing to do so, in the words of the overseer, would have meant nothing less than “white slavery” (26-27).

White piety formed the beating heart of the white Christian commitment to lawlessness for the sake of plunder, facilitating widespread white criminality under the guise of paternalism—the “care” of enslavers for those they enslaved. Their depraved devotion led Douglass to conclude that the act of enslaving had a corrosive effect on white enslavers and their communities. Enslaving transformed white Christians—both enslavers and the majority of white Northerners who failed to act against slavery—into degenerates, incapable of goodness and virtue. When Douglass was sent to work for Hugh Auld in Baltimore, for example, he found that Sophia Auld, who had not grown up around slavery, was caring and supportive relative to other enslavers. “She had bread for the hungry, clothes for the naked, and comfort for every mourner, but slavery soon proved its ability to divest her of these heavenly qualities.” She eventually “became even more violent in her opposition than her husband himself.” Slavery, Douglass concluded, “proved as injurious to her as it did to me” (32-33, 34-35). Just as the force and lawlessness required to operate slavery was diffuse, so too were the spiritual harms of American Christianity, transforming American Christians into disciples of mass harm.

In Narrative, Douglass gave white Americans a shocking rendering of American Christianity, one that revealed the self-declared righteous and godly as rapists, human traffickers, torturers, plunderers, and murderers. In fact, these acts of depravity went hand-in-hand with the devotion of American Christianity, projecting white piety as a tool to aid in the accumulation of persons, property, and power to the glory of God. The white piety that governed American society wove lawlessness into the law and immorality into goodness and virtue. It positioned men like Covey and Thomas Auld as devout practitioners of the most fundamental belief of American Christianity: that the torture-for-profit system of slavery represented the highest possible good. At best, white American Christians were complicit by law and custom in these crimes. At worst, they were their perpetrators. As Douglass observed, “the man who wields the blood-clotted cowskin during the week fills the pulpit on Sunday, and claims to be a minister of the meek and lowly Jesus” (85-87). “To be a friend of the one,” he concluded, “is of necessity to be the enemy of the other.”

William Horne is a historian of white supremacy and Black liberation at the University of Maryland, College Park.

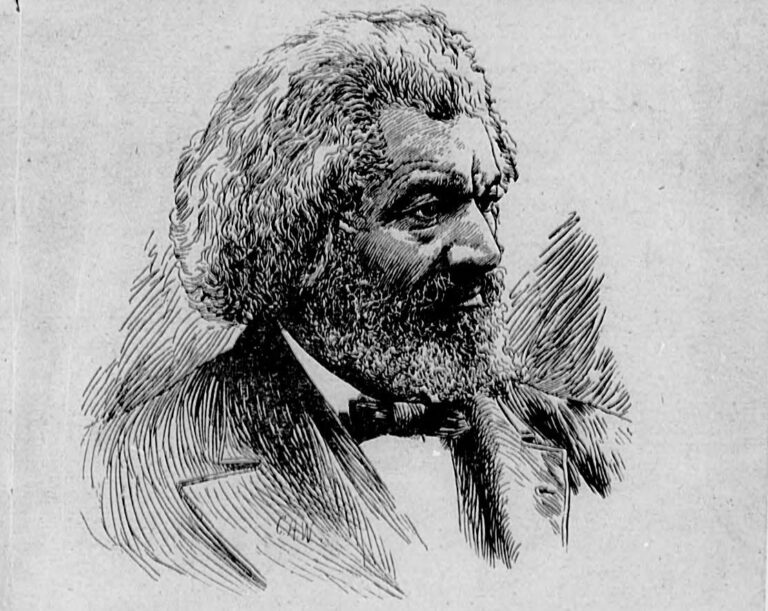

Photo Credit Line: Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, The Frederick Douglass Papers at the Library of Congress