Now with their hands held high, they reached out for the open skies

And in one last breath they built the roads they’d ride to their death

Driving on through the night, unable to break away

From the restless pull of the price you pay

– Bruce Springsteen, “The Price You Pay”

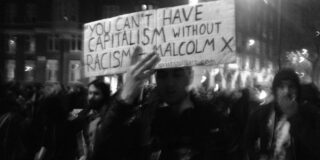

To many religious and political conservatives, critical race theory and intersectionality make up the two-headed bogeyman of the 21st century. This monstrosity threatens our “colorblind” society, branding all white people as racists and seeking to restore racial hierarchy — but this time with victimized minorities on top and whites on the bottom. For me, however, internalizing critical race theory and adopting an intersectional analysis for resisting injustice in America helped me gain an appreciation for the boogie man: Bruce Springsteen.

I began listening to Springsteen during a period of my life when I felt like I had nothing left to lose. I was stuck in a dead-end job, having a crisis of faith, being harassed by the police, and becoming increasingly disillusioned by arguments insisting that white voters elected Donald Trump simply because they were predestined to be racists. This turned out to be the perfect moment for me to meet Springsteen and his songs’ characters.

I promise this essay is about critical race theory and not a Bruce Springsteen hagiography. While Springsteen’s acclaim is well-deserved, he also deserves critical political assessment. As mesmerizing and textured as Springsteen’s characters can be, Springsteen himself is so astonishingly wealthy and such a liberal darling that it’s hard to believe the same person who admitted to dodging the draft hosted a podcast with the former Commander-in-Chief — or that he did the Super Bowl ad my sister refers to as “God, Country, Jeep”.

Springsteen is compelling to me not for his politics, but for two different, interconnected reasons. First, the novelty of someone like me — at first, adamantly opposed to Springsteen — experiencing a paradigm shift after closely engaging his lyrics instills hope for myself and the whole lot of humanity (exceedingly rare for me on both counts). Second, Springsteen has a keen ability to expose systems of oppression while simultaneously articulating a clear, relatable, universal hunger for justice — something that should interest writers and activists alike.

As with all great musicians, artists, and writers, when I listen to Springsteen, I am reminded that there are systems that want to divide us and swallow us up, in the same way they divided Springsteen’s characters Le Bin Son and Billy Sutter. At the same time, I’m reminded that we possess the tools to confront those systems and that through that confrontation, we can imagine a society where the ghost of Tom Joad can finally rest.

Talk of “confronting systems of oppression” often seems abstract because the theories and activists confronting these systems have been intentionally obscured. This is the darkness on the edge of town (a term I’m using metaphorically, not racially). The practitioners of critical race theory, who for decades remained marginal and have now been thrust onto the public scene, are trying to hold up our history and cajole us into imagining a new way of relating to one another so that whiteness won’t be the death of us.

Critical race theory, and the related theory of intersectionality, are essential tools for developing collective, multiracial solidarity. They are tools we must use to imagine a new kind of human relationality. But there are powerful groups of people who’d prefer that we remain docile.

Critical Race Theory Exposes the Price We Pay

Perhaps I’ve completely alienated you with my introduction. Or maybe you’ve continued reading because you’re certain I know more about Springsteen than critical race theory. There’s only one way to find out.

Knowing nothing about critical race theory while commenting on it authoritatively or making laws banning it in public schools is certainly in vogue. Rep. Steve Toth (R-Texas) wrote H.B. 3979, which would require teachers to offer a “both sides” perspective on topics such as slavery or the genocide of Indigenous people. Rep. Chris Pringle (R-Ala.) gave voice to perhaps the most widespread caricature of critical race theory, arguing that it should be banned because it “teaches that certain children are inherently bad people because of the color of their skin, period.” In an effort to “cap discussions of critical race theory,” Tennessee has passed legislation that could potentially withhold millions of dollars from schools that teach about issues relating to racial divisions or inequality in America. And Tennessee’s governor, Bill Lee (R-Ten.) recently asserted that critical race theory is “un-American.”

A number of prominent Christian conservatives have also jumped on the bandwagon, as part of a larger attempt to stem the tide of critical theory and “wokeness” in churches. Through myriad books and conferences, as well as theological critiques of “critical theory,” Christian conservatives and evangelicals have contributed to anti-critical race theory propaganda in their own way, and to great effect.

So, what is critical race theory and why are wealthy politicians, megachurch pastors, and conservative theologians trying so damn hard to turn the masses against it?

Critical race theory emerged as a distinctive form of legal scholarship in the 1970s and 1980s, offering an explanation of why racial inequalities persisted in the post-Civil Rights age. Although legislation like the 1965 Civil Rights Act established formal racial equality, critical race theory scholars peeled back the facade of “colorblind” jurisprudence to reveal how legal systems and specific laws continued to perpetuate racism. Activist-scholars like Derrick Bell, Richard Delgado, and Kimberlé Crenshaw articulated a niche but compelling account of how “race-blind” legislation and policies continued to perpetuate racial inequalities. Rather than reducing racism to individual prejudices, critical race theory emphasized the structural effects of the centuries-long legacy of American slavery, insisting that the historical relegation of Black people to second-class citizens embedded racism in contemporary education, housing, banking, and penal practices.

This previously obscure — and often boringly technical — legal theory has suddenly mutated into a bogeyman because, as David Theo Goldberg writes, it is now being “expanded and applied more generally to social discourse and practice.” Commenting on the tenure controversy surrounding Nikole Hannah-Jones, Jelani Cobb notes that critical race theory has entered our “social discourse” because “progressive white scholars and scholars of color have spent the past several decades fighting for, and largely succeeding in creating, a more honest chronicle of the American past.” We should add that it is also thanks to artists, activists, and working-class people that critical race theory has slowly crept from the margins into the mainstream.

The push for a more honest narration of American history has been met with intense pushback— specifically, with accusations that critical race theory is “anti-white people.” As Christine Emba writes, “Critical race theory has been purposely mischaracterized as a divisive form of discourse that pits people of color against White people.” We shouldn’t be surprised by this bad faith presentation of critical race theory. Since Reconstruction, the threat of interracial democracy has always produced strong racial reactions from whites, who mobilize around fears of “reverse racism” and victimization at the hands of emancipated Black people.

But the proliferation of confusion about critical race theory isn’t only due to white supremacist and right-wing propaganda. Supposed acolytes, self-proclaimed antiracists, and vocal “allies” also do a grave disservice to critical race theory when they frame discussions about American injustices, past and present, exclusively in terms of racial identity, rather than adopting an intersectional approach.

Intersectionality is sexy. No, not the actual theory, but the practice of sprinkling the word in here and there during a conversation over mimosas. The actual theory, first developed by Crenshaw, insists on analyzing the multiple identities that “intersect” an oppressed person, and how those intersecting identities can render a person more vulnerable to injustice. Rather than reducing oppression to one primary identity, intersectionality analyzes race, gender, sexual, and class identities together. This approach is indispensable because it creates opportunities for people and groups divided by oppressors to recognize shared material interests, setting the stage for mass movements of solidarity.

Intersectionality does not preclude “white people” from these movements of solidarity because they are white. In fact, intersectionality insists that those racialized as white are themselves marred and demeaned by racial systems. The same racial system that degrades Black life also traps white people, exploiting their identities and labor for economic interests that they are told they have “access to,” but rarely, if ever, access.

This is the insight that megachurch pastors and wealthy politicians don’t want their flocks to get hip to. Critical race theory and intersectionality invite white people not only to interrogate their racialized identities, but to interrogate why those identities exist in the first place. To see the con of whiteness — the harm it does to both whites and racial minorities — might just move white people to join with other marginalized people to imagine a new society beyond racialized identities. Embracing this paradigm would put megachurch pastors, the wealthy, and perhaps even “order” itself out to pasture.

I told you this would be an essay about critical race theory, not Bruce Springsteen. And if I have at least convinced you of that, now let me try and convince you of this: critical race theory’s opposition to “whiteness” has nothing to do with hating white people, but with opposing an ideology of economic fallenness.

Paying for the Sins of Somebody Else’s Past: The Fall

Mainstream accounts of economics focus almost exclusively on how atomized human beings allocate and exchange scarce resources. But economies are always embedded in day-to-day social and political relationships. Economies are also inherently structural, as they are developed from what humans deem to be order. So where there is a perversion of human relationships, that perversion permeates social systems.

Critical race theory makes this perversion legible, revealing how the ordering of humans along racial lines — through colonialism, chattel slavery, Jim Crow laws, and the War on Drugs — continues to produce structural, systemic inequalities. Economic inequality, too, is a product of “whiteness.” As Emma Dabiri suggests, “The idea of a white race was invented to create a narrative, and to enshrine into law the rights, the superiority, and the access to opportunity and resources for people racialized as white, and to subjugate Black people.” This is not to say that all people racialized as white have had a hand in inventing this system, or that they have wholly benefited from it. But because this racial order continues to reverberate, those who Phil Christman identifies as “whitened” are still disproportionately favored.

In his book, The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race, Willie James Jennings provides an early example of racial ordering by attending to the racial terms used by the Spanish. The nomenclature of “white” was created to establish sharp divisions between who was human and subhuman, who was saved and damned, who was ordered and disordered. “White people” were not so designated because of their nationality or pigmentation. White people became white through a material process of colonization, which gave rise to what Jennings calls the “racial gaze.” This racial gaze became not only a social paradigm, but a theological paradigm, as whiteness acts as a “co-creator with God,” facilitating “an inverted, distorted vision of creation” that manifests itself in the myriad “mangled spaces” of human interaction. The racial gaze established an economy where “white” came to be synonymous with human agency, systemic power, and divine sovereignty. It is this racial gaze, and the power ascribed to the “whitened” body as well as its body politic, that continues to bear the strange fruit of an economy of whiteness.

Senator Marsha Blackburn (R-Ten.) inherits and wields this whiteness. She is one of thirty-nine other Republicans who signed a letter to Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona, denouncing critical race theory as “divisive.” The signatories argue that to suggest this nation was founded on whiteness is to openly invite “anti-white” sentiment, even anti-white violence. But violence is already being done to white people, and the perpetrators are not critical race theorists, Black people, or the Left. The perpetrators are people like Sen. Blackburn, who has taken obscene amounts of money from pharmaceutical companies while white people lead Tennessee in opioid overdoses. That Sen. Blackburn can denounce critical race theory as anti-white while aiding and abetting multi-billion-dollar companies as they kill her white constituents demonstrates how this economy of whiteness will even contradict itself for capital gains.

Contradictions like this convinced me James Baldwin was right when he insisted that whiteness is a “metaphor for power.” Stefano Harney and Fred Moten take it one step further: “Governance is the extension of whiteness on a global scale.” Critical race theory seeks to expose how this white-power orders, extracts, and benefits the few at the detriment of the many. Even white people can get caught in its maw. Therefore, whiteness, and the economy it begets, must be recognized as fallen.

I invoke theological imagery intentionally because I believe theology can add something to critical race theory. Theology, too, provides a way to describe the political machinations that shape our world and encourages humans to imagine political alternatives, however “unrealistic.” So, we imagine there is A Love Supreme that exists both in humanity and independent of humanity, a Love that beckons us toward a new, unexplored existence where society is shaped by collective solidarity and economic justice. But while this Love is ultimate, there is a penultimate distortion in the world that Christian theology attributes to the Fall (Genesis 3). This distortion is not just spiritual, it is lodged in human interactions, historical systems, and political structures.

Neither the fallenness of our societies nor our individual brokenness forecloses the possibility of humans collectively struggling for the common good. In The Death of Race, Brian Bantum explains that if humanity is to counteract the results of the Fall, we must acknowledge “how differences become distortion and [how] these differences are hewn into fortresses, structures of human civilization that destroy so that some may live.” Bantum then makes this critical point, “To see the possibility of freedom, we must see the contours of our bondage.” We all suffer under the bondage of whiteness; freedom will only come in recognizing the depth of this distortion. We have been authorized to collectively rebel against systems that order people for death. Whiteness is such a system and it will take an intersectional movement of people of all identities to defeat it and imagine a new human economy.

Ties That Bind: An Economy of Darkness

Intersectional movement-building, unlike the word “intersectionality,” is not sexy. Building coalitions is a painstaking process, one made even more difficult by liberal “antiracists” who have popularized the idea that white people are hopelessly fragile and totally depraved in their racism — that they are damned to be white. All they can do is “transfer their privilege,” “decenter” themselves and get out of the way.

Rather than seeing “whiteness” as a socially constructed system of division that can be overcome, much liberal antiracism doubles down on racialized identities, equating white skin with an unalterable predisposition to oppress Black people. And because liberalism tends to separate racial oppression from economic inequality, this kind of antiracism offers little engagement with class and capitalism. It thus fails to see points of shared material interests between whites and other racialized minorities. While often cloaked in the language of critical race theory, liberal antiracism is popular because it demands no transformative change.

A favorite author of liberal antiracists is Ta-Nehisi Coates. In his influential essay for The Atlantic, “The Case for Reparations,” he persuasively argues that white supremacy has “plundered” America’s Black citizens throughout the nation’s history. But while Coates’ argument for reparations is convincing, his analysis of why this economy of plunder was established, and how it continues to operate today, is . Coates does not want economic explanations to substitute for racial ones. So when it comes to disparities between Blacks and whites, Coates writes that, “to pretend that the problems of a dual society are the same as the problems of unregulated capitalism is to cover the sin of national plunder with the sin of national lying.” For Coates, the force of white supremacy can operate independently of specific material interests. After all, many white people derive psychic satisfaction — rather than clear material advantage — from investing in anti-Black, racial hierarchies.

But while Coates persuasively shows how white supremacy facilitates the material plunder of Black people, he ironically contradicts his claim that white supremacy can operate independently of any specific interest. It’s true that Blacks have been materially dispossessed as a result of white supremacy. But white supremacy must be seen as a primary mechanism of racial capitalism — or as I’ve been calling it, the economy of whiteness. Coates’ liberal emphasis on white identity politics gets one thing right: some white people do embrace white supremacist ideologies despite the fact that they receive little to no material benefit. But they embrace this ideology because of a learned history, one that establishes them as authors of a social order that necessitates the material plunder of racialized minorities.

Understandably, Coates wants to dismiss white leftists who consider anti-racism an unnecessary distraction from class struggle. But in his haste to homogenize leftist perspectives on economic exploitation he fails to explain how white supremacy and racial capitalism are concretely related. The Black radical tradition, for example, has shown that leftists need not be class reductionists who oppose anti-racism. This tradition advanced a powerful criticism of capitalism that did not reduce race to class. Following this tradition, it becomes clear that whiteness will only be abolished when “whitened” people begin embracing intersectional solidarity over and against the economy of whiteness.

Although I do not share Christman’s misgivings about using terms such as “abolish whiteness” or agree that the term “white/ness” evades a clear definition, I wholeheartedly agree that we must push conversations on race and class toward a more constructive and inclusive vision for justice. But where do we look? How do we develop a new paradigm?

On the outskirts of American politics, activists and scholars who have largely been excluded have continued imagining alternative economies, even in their exiled darkness. It is in these places of darkness and disorder that we may just find our future as a species.

The scholars and activists who imagine this future have been forced into ghettos (both literally and figuratively) or have taken up residence in the “undercommons.” This is because their visions of multiracial class solidarity, and the powerful movements they have inspired, are anathema to whiteness. The Movement for Black Lives, a coalition-building movement founded in 2015, is rooted in older, visionary projects like Fred Hampton’s Rainbow Coalition and Martin Luther King Jr’s Poor People Campaign. Both men were assassinated by the state because, in their commitment to multiracial struggle, they dared to turn white people against the system that made them white.

These powerful examples of multiracial solidarity are proof that the movement for Black liberation is not predicated on hating or excluding white people. The same lie that is peddled against critical race theory has been wielded against historic Black freedom movements: that Black liberation is necessarily anti-white and is not interested in improving the material conditions of white people. Not only have Black scholars like Crenshaw and Robin D.G. Kelley disproved this lie over and over again, but they have forcefully demonstrated that being whiteness does not necessarily protect white people from social degradation. Coalition-building with white people must continue, even if the history and accomplishments of these movements is despised or forgotten.

The scholar-activist Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor has continued and refined the tradition of the Black radical imagination, and believes coalitions must focus on issues that impact the entire working class, while still giving special attention to the way race operates. Stark wealth disparity and the (mis)use of public funds are issues that have mobilized many across racial lines, as they start to see how the current economy is built on the extraction and plunder of the many for the sake of the few. Taylor points out that the summer protests of 2020 show the beginnings of a coalition of activists who are demanding material changes that move beyond “reform” and “representation” and toward the abolition of an economy that thrives on alienation and predation.

Taylor’s vision for liberation is inclusive of Black and white people, as it imagines all oppressed people struggling together against a common enemy to transform society. In this vision, Black and white people identify common issues and interests that would concretely benefit racialized whites and non-whites. Taylor notes, for instance, that “alcoholism, opioid abuse, and suicide” are driving a marked decline in life expectancy among white people. This decline is not due to Black people, critical race theory scholars, or “cultural Marxists.” It is a direct result of the market of whiteness contradicting itself in order to do away with the refuse that is the white, working class.

Taylor sees that young white people have begun to notice that the same economy of whiteness that leaves them without a future also spins on the axis of anti-Black violence, which has compelled them to join with Black people in protest. For Taylor, the “success or failure” of imagining a new human economy depends on whether people can see one another “as brothers and sisters whose liberation is inextricably bound together.” This alternative economy, informed by the Black radical tradition, is what I would call an economy of darkness. Again, I’m using the term darkness metaphorically, not racially.

Perhaps what we’re after can’t even be cloaked in a term like “economy.” What is needed is a radical break from the ordered ways of thinking that whiteness has imposed on us. Breaking from whiteness will lead to darkness. In that darkness, we can move toward a society that imagines revolutionary relationality. This dark revolution, if it’s to occur, will be driven by a mixed-multitude. This is somewhat tongue and cheek, but I am sure that it’s this darkness that inspired Springsteen to write the fleshy fantasy he dubbed, “Dancing in the Dark.” No one will convince me otherwise.

* * *

We can either dance in this darkness or perish as a species. The road to extinction begins with banning theories and then, the next thing you know, we’ll see the skyway bedazzled with bombs galore. Soon after, the only thing left of us will be our particles drifting through space which would at least allow us to return to dust as a collective. Maybe then, out in this eternal Om, we’d finally rest in that intangible yet all-encompassing thing called darkness. Maybe that’s God. A fate like that may read a weird bit like gospel but nothing in this paragraph is prophetic.

I’m certain humanity will dance in one sort of darkness or the other. I’m on the record for which darkness I prefer, but it will take all of us to derail this race car off the race road of death if we’re to get where no person has yet been. I guess ultimately, whether it’s by the skyway or my way, I know we’ll all be boogiein’ in the dark for an eternity.

Dedicated to the teachers who taught me the dark arts: R.A.D and M.B.

Josiah R. Daniels is the associate opinion editor at Sojourners. Although he is neither a musician nor a detective, he would classify his writing style as both “hard-bopped” and “hard-boiled.” You can read his essays at Religion Dispatches, Geez Magazine, and Sojourners to see if you agree. Follow him on Twitter: @josiah_Rdaniels.