This essay adapts material from Gary Dorrien’s book American Democratic Socialism: History, Politics, Religion, and Theory, forthcoming in September 2021 from Yale University Press.

DEMOCRATIC socialism is a stronger factor in U.S. American politics today than at any time since Eugene Debs won 6 percent of the national vote in 1912. Debs, the icon of American socialism, ran for the presidency five times. Norman Thomas, a former Presbyterian minister and for forty years the tribune of “Norman Thomas Socialism,” ran for president six times. Michael Harrington, America’s leading Socialist from 1964 to 1989, absorbed the lesson of Debs and Thomas that running for president is too humiliating to be worth it. Harrington taught democratic socialists to operate in the Democratic Party, building up its coalition of unionists, racial justice activists, feminists, environmentalists, progressives, and vanilla liberals. Bernie Sanders, running in 2016 the greatest presidential campaign ever conducted by an American socialist, vindicated the Harrington strategy, which was never that Socialists should be content in the Democratic Party.

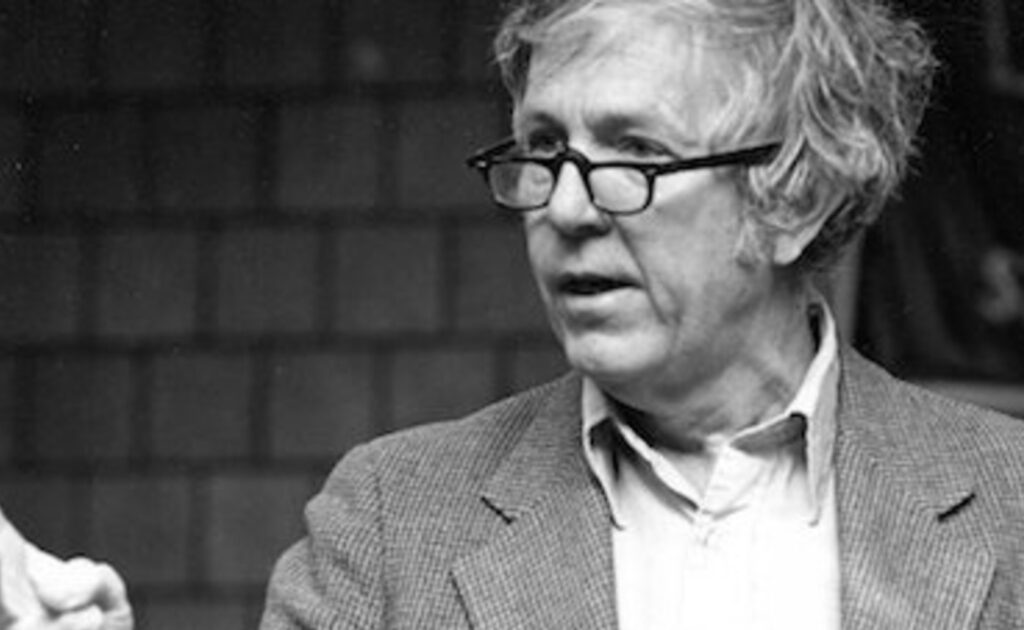

Of the four foremost American socialists, Harrington is the least known and the only intellectual. In the early 1960s, he had a spurt of fame for writing a landmark critique of American poverty, The Other America. In 1973 and 1982 he responded to the political wreckage of his time by founding two social democratic organizations, the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee (DSOC) and Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). Today DSA is stronger than ever, though its largest caucuses have disavowed Harrington’s social democratic approach to socialism. Harrington came from the tiny generation sandwiched between the Old Left of the 1930s, which fought over Communism and for industrial unionism, and the New Left of the 1960s, which spurned the Old Left fixation with Communism and unions. He tried to bridge the chasm between these two generations, and failed spectacularly, before he tried again with modest success. Uniting the democratic Left through democratic socialism was a storied, frustrated, long-running dream of American Socialists. Harrington kept it alive before Sanders and the ravages of neoliberalism dramatically revived it.

Harrington grew up in St. Louis, Missouri, where his middle-class family was Irish Catholic on both sides and his formidable mother was dogmatically Catholic. Precocious and eager to please, he started high school at the age of twelve, studying under Jesuits in St. Louis and at Holy Cross College in Worcester, Massachusetts, always the youngest in his class. His training in Thomist scholasticism showed through for the rest of his life, yielding three-point lectures, syllogisms, and a powerful attraction to Marxian scholasticism. Worcester was a cultural shock to him because he grew up in assimilated Midwest Irish-Americanism, unprepared for hardened ethnic enmity. In Worcester, Harrington met Irish-Americans whose memories of persecution centered on New England, not Ireland. They hated the Yankees who had driven them to a sullen ethnic chauvinism that looked down on Jews, Blacks, Italians, Lithuanians, Poles, and all non-Irish Catholics.

He proceeded to a year of law school at Yale, which bored him, and a year of English literature at the University of Chicago, which he liked, but not enough to hang on for a doctorate. At Yale, Harrington rebelled against Irish Catholicism by becoming a Taft Republican. On his last day at Yale, as he told the story, he switched to democratic socialism, later vowing during a summer job to devote his life to obliterating poverty. The Korean War began in 1950 and Harrington joined the Army Medical Reserve, but the reserves were not called up and Harrington transferred in January 1951 to a unit in New York. He found his way to the Catholic Worker House on Chrystie Street in the Bowery, where he met its legendary founder Dorothy Day.

Catholic Workers were committed to voluntary poverty and serving the poor. Harrington took over the newspaper, winning over Day with his boyish affability and brilliance. Day had a colorful past as a Bohemian Greenwich Village radical, but shushed Workers who asked about it. She broached no dissent from Catholic orthodoxy or her personal authority. At the time, Day was deeply embattled because of the war. In between wars, the Worker surged and the Catholic hierarchy put up with Day’s radicalism. Every time there was a war to oppose, the Worker lost followers and readers, and Day fended off attacks from bishops.

FOR nearly two years Harrington tried to adopt Day’s anarcho-pacifism and her Catholic orthodoxy, while spending his evenings at the White Horse tavern. Dylan Thomas, Delmore Schwartz, Norman Mailer, William Styron, Dan Wakefield, and other poets and writers were regulars at the White Horse. Young Democratic Party operative Daniel Patrick Moynihan was another regular. Harrington wrote poems about Bohemian freedom, drank every night, held court on politics and literature, and became a fixture at the White Horse, dropping Day’s anarchism, pacifism, and religion in succession.

Bogdan Denitch spotted Harrington on a picket line in March 1952. Harrington looked misplaced to him among the Catholic moral perfectionists, so Denitch recruited him to the Socialist Party’s youth division, the Young People’s Socialist League (YPSL). Denitch was a Serb from Kosovo born in 1929 in Sofia, Bulgaria, where his father was the Yugoslav ambassador until the Nazis drove him into exile during World War II; later he was exiled again by Marshal Josip Broz Tito’s Communist regime in Yugoslavia. Denitch fought in a Yugoslav unit in the British Eighth Army, was wounded in Italy, served with the British occupying forces in Vienna, and had bruising encounters with the Red Army. After the war the British government asked him to fight insurgents in Malaya or mine coal. Denitch’s military service entitled him to first class passage anywhere in the British Empire, so he chose Canada instead, proceeding in 1946 to City College in New York. There he revived YPSL’s lost art of aggressive organizing. Denitch was exuberantly promiscuous and dramatic, exuding a bluff, garrulous, gunslinger style, enticing female admirers with highly fictional tales of his resistance adventures in Yugoslavia. The Socialist Party was too tame for him, and splitting YPSL was almost too easy. He and Harrington took most of YPSL into the Shachtmanite camp, deeply offending Norman Thomas.

Max Shachtman, a former lieutenant of Bolshevik hero Leon Trotsky, broke from Trotsky in 1940 to found the Workers Party. He was colorful, intellectual, and cunning, oscillating between cheeky banter and heroic exhortation. He enthralled his cult with witty, powerful, comical platform performances, gyrating through Marxist theory and current history, reeling off dramatic litanies of the Socialist comrades murdered by Stalin. He could also be mean, ridiculing his disciples behind their backs, which made them fearful of becoming the next target. During and after World War II the Workers Party opposed capitalist wars, condemned Stalin’s imperialism in East Europe, supported Black revolutionary movements, and defended striking CIO unions. It called itself a “Third Camp” revolutionary Socialist party, opposing capitalism and Soviet tyranny. Shachtman attracted brilliant Lefty types who found Thomas boring: Ernest Erber, Irving Howe, Julius Jacobson, Hal Draper, Gordon Haskell, C. L. R. James, Dwight Macdonald, Earl Raab, and Philip Selznick. They outshone the Thomas Socialists from the left and were skilled at Marxology.

The Shachtmanites retained their sectarian fervor into the 1950s, proclaiming portentously about the sweep of history and the demands of the age. But now American capitalism was booming, necessitating evermore reliance on sectarian obsession. In 1949 Shachtman renamed his group the Independent Socialist League (ISL) and dropped its membership in the Trotskyite Fourth International. ISL supported the purge of Communists from the CIO and aligned with European Social Democratic parties, which raised the question whether Shachtman was still a Leninist. He wasn’t sure. Meanwhile the Socialist Party rolled over for the Korean War, rationalizing that it was a test of anti-Communist containment and the United Nations. Harrington resented that fellow Socialists wanted him to kill Koreans.

In 1954 he and Denitch founded a Shachtmanite youth organization, the Young Socialist League (YSL). Harrington absorbed the Marxian fetish with being hard, though YSL stalwarts never thought he was hard like them: How hard could he be if he came from the Catholic Worker and wrote for Commonweal? A cult of Marxian hardness and dread of feminine everything prevailed in Old Left culture. The Socialist Party and the ISL welcomed female members without asking how they felt or what they wanted. The women who joined were usually students or recent college graduates, often with backgrounds in religious service. They signed up for organizing tasks, typed stencils, handed out leaflets, spoke up in meetings (or not), and did not complain about sexist male leaders. The movement as a whole had an ethos of ascetic self-sacrifice. Women could not call attention to their needs without suggesting that they lacked the requisite self-sacrifice. The Socialist Party of the Debs era had questioned why women should have their own caucus, but at least it raised up female leaders and accepted a women’s caucus. Now the party didn’t ask if something was missing.

Until 1954 Harrington held the usual Socialist view that anti-racist activism, though important, was not a top priority. He looked down on the NAACP as a vehicle of the Black bourgeoisie. Meanwhile, the few Black Americans he knew personally were Socialists, notably A. Philip Randolph, James Farmer, and Harrington’s friend Bayard Rustin. Harrington felt vaguely that Randolph, Farmer, and Rustin hit on something important, whatever it was. He conjectured that the struggle against racism might be the next great “Social Force” in U.S. American politics. Then lightning struck in Montgomery, Alabama in December 1955 and Rustin knew what it meant. The struggle had returned to the South, it was not based on unions or the NAACP, and it ran through the Black church. Harrington worked on all the mobilizations of the 1950s that Rustin directed from Randolph’s Harlem office.

By January 1956 the American Communist Party was down to 20,000 members, which was still larger than the entire organized anti-Stalinist Left. The following month Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev condemned Stalin as a paranoid mass-murdering tyrant. His secret speech, published in June, set off a stampede from the Communist Party, reducing it to a shell of 3,000 members jostling with FBI infiltrators. Shachtman urged his disciples to think about where all those ex-Communists might go—perhaps a new configuration was possible. Young David McReynolds, a Socialist Party pacifist, came up with a plan: Why not merge with the Shachtmanites? Then perhaps the disillusioned Communists would be willing to come aboard.

McReynolds pitched this proposal in 1956 to the Socialists, who rejected it resoundingly by more than three-to-one. How could they work with Leninists? Why would they want to? McReynolds pleaded for two years that Shachtman had changed; a merger would energize the party. Thomas hedged, telling McReynolds he would accept the Shachtmanites except Denitch and Harrington, two connivers he couldn’t stand. Shachtman begged to be admitted, promising not to capture the party. He made a goodwill move by shooing Denitch to Berkeley, California, which prompted Thomas to support the merger plan.

The merger passed by a narrow margin became many still feared that Shachtman was not a democratic socialist. They had no idea that he was hurtling toward the party’s right flank—the stodgy, grumpy, fiercely anti-Communist Old Guard faction. In 1958 Shachtman cared about one thing—currying favor with the Old Guard. This was a group he could dominate for the rest of his days. The Shachtmanites swiftly took over the Socialist Party publications and the youth organization while falling short of a majority on the national committee. Young activists from the civil rights and antiwar movements came into the party lacking any concept of an Old Guard Socialist or a Shachtmanite. They were surprised at what they encountered when they joined; it wasn’t like the Harrington speech at their college.

The Shactmanites entered the Socialist Party with a vision of a realigned Democratic Party that supported the civil rights movement and drove out its Southern segregationist leaders. There were too many liberals wasted in the Republican Party and too many Dixiecrats thwarting the Democratic Party. If Southern Blacks got to vote again, and the newly merged AFL-CIO used its political muscle, a new Democratic Party would emerge. It needed to become the natural home of all labor voters, civil rights activists, progressives, Socialists, farmers, and liberals. Harrington was one of the last Shachtmanites to accept this argument, because emotionally and intellectually, he couldn’t bear the thought of voting for a Democrat. Weren’t they still Marxists?

THE student sit-in explosion of January 1960 unleashed a flood of civil rights demonstrators who set off protest wildfire and challenged King to get arrested with them. King had only talked about Gandhian disruption, without doing any. The student protesters put their bodies on the line and reignited the civil rights movement, founding the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Another storied New Left organization, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), also arose in January 1960. It was founded by a Socialist Party offshoot, the League for Industrial Democracy (LID), and based on the University of Michigan campus. Meanwhile the Shachtmanites stopped denying that they were running the Socialist Party. At the Socialist convention of May 1960 they declared that the civil rights movement and AFL-CIO were transforming the Democrats into a labor party. Seemingly overnight, the Socialists had developed warm feelings for liberals and a sunny optimism about American politics. They were done with planting a flag in the wilderness, wholly committed to realigning American politics.

King and Randolph called for demonstrations at the upcoming Democratic and Republican Conventions, which they named the March on the Conventions Movement for Freedom Now. The organizing burden fell on Rustin, who turned to Harrington. Rustin sent Harrington to organize the protest at the mid-July Democratic Convention in Los Angeles. Harrington went to Los Angeles imbued with a romantic image of himself and was swiftly disabused of it. The desolation of Black life in Los Angeles stunned him. He thought constantly about James Baldwin’s saying that a Black American must always be on guard and never relax. Harrington saw it like never before, fretting that he was edgy and defensive in Los Angeles. Black New Yorkers lived in sprawling tenements that fostered a sense of community. In Los Angeles, Blacks were spread out over huge geographic distances in decaying individual houses. Harrington winced at the isolation and anomie he encountered. He caught his first glimmer of a self-recognition that haunted him for years—his simple belief in racial integration rested on the false assumptions that he was good, White society was normative, and Black Americans wanted to be assimilated into White society. For six weeks Harrington worked around the clock to organize a march. For five weeks he failed, until he pulled off a march that was just big enough not to be embarrassing.

There he witnessed King’s constant bombardment. King told him he was leaning toward John Kennedy, and Harrington urged him to hold back. Years later, this was one of Harrington’s favorite stories. He would recall that he had a stupid reason and a good one—he hadn’t adjusted to supporting any Democrat, and Richard Nixon might win the election. Neither party deserved the votes of Black Americans, but King surmised that Kennedy might be the best bet. They turned to political philosophy and Harrington gasped at realizing that King was a flat-out democratic socialist. King was not merely influenced by Social Gospel socialism or his friendship with Rustin. His worldview was democratic socialist, a vision of economic democracy. Harrington felt anxious, and then a flash of ideological pride. This could not get out; it would ruin the movement if people knew that King was a Socialist. Harrington did not want to hear King say it, while delighting that he and King were comrades.

The New Left ascended dramatically, bristling with the idealism of privileged youth. It brought the first wave of the baby boom generation into Left politics by defying the complacency and parental conformism of the 1950s. Two conventions of June 1962 framed the attempt of the Old Left to bond with the new generation. One was the Socialist convention in Washington DC, where the party formally settled that it was committed to the realignment strategy but not exclusively; nobody had to work with Democrats unwillingly. The second was the SDS convention in Port Huron, Michigan that issued the Port Huron Statement.

The New Left ascended dramatically, bristling with the idealism of privileged youth. It brought the first wave of the baby boom generation into Left politics by defying the complacency and parental conformism of the 1950s.

SDS leader Tom Hayden wrote the first draft of the SDS manifesto, a stew of liberal humanism, anti-anti-Communism, and participatory democracy. Fifty-nine members of SDS convened in Port Huron to revise it. On the opening night, Harrington blasted Hayden for dismissing anti-Communism, the labor movement, and liberal Democrats. Hayden replied that America used anti-communism to excuse every bad thing it did in the world. He didn’t believe the Soviet Union was inherently aggressive or that American troops belonged in Vietnam. Moreover, most unions were conservative, and liberal Democrats were part of the problem. Otherwise, what was the point of creating SDS?

Harrington came off as an Old Left bully. To him the Red Army smashing into Hungary in 1956 was a fresh outrage compelling condemnation. Nobody in SDS shared that feeling. Harrington said realignment was the key to changing America, and liberals were essential to it. It didn’t matter that his group adopted this position only recently. The Shachtmanites had let go of their Marxian cynicism about electoral politics. They became optimists during the very years that Hayden’s generation discovered that the USA was surprisingly bad. The ironies sailed past each other at Port Huron. The Marxian Socialists wanted to renew the Democratic Party from within and the recently alienated SDS youth wanted an alternative to Democratic Party liberalism.

SDS touted its distinct experience and college student outlook: “We are people of this generation, bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably to the world we inherit.” The delegates said they were raised to believe that America stood for freedom, equality, and democracy. They told a story of disillusionment centered on the persistence of racial bigotry and the threat of nuclear war. They called for a generous individuality that nurtured a caring and democratic society: “We would replace power rooted in possession, privilege, or circumstance by power and uniqueness rooted in love, reflectiveness, reason, and creativity.”

Harrington had to leave the conference after the first night and did not realize that SDS tried to accommodate his criticisms. He pressed the LID board to void all decisions made at Port Huron, fire Hayden and other staff, and censure SDS materials coming from the LID office. He believed he was curbing some unruly youngsters much like Thomas dealt with Denitch and him in 1953. It took Harrington several weeks to realize he had blown an historic opportunity. SDS leaders couldn’t look at him, his reputation plummeted on the Left, and embarrassment swept over him. He was humiliated, having failed to perceive the difference between SDS youths trying out a position and Old Left faction fighters holding a line. His early apologies said he made some important points about Communism in a bad way. Later he said he was blind and dense in ways he found inexplicable. Still later his therapist helped him comprehend that SDS refuted his self-image as a young leader with good ideas.

HE never got over it. The fallout dogged Harrington for the rest of his life, lingering wherever he went on lecture tours, yielding hostile questions he fielded with apologies that sometimes ran too long. SDS founders nurtured their victim story beyond its reasonable shelf life, refusing for over twenty years to accept his apology, fueling a leftwing tradition of Harrington-ridicule. But contrary to exaggerated versions of this story, Harrington did not destroy his legacy at Port Huron or lose his relationships to the New Left. He spoke to SDS chapters through the years of his grapevine beatings, even as he stuck to his baseline points about Communism. Meanwhile SDS descended into revolutionary delusions that destroyed the organization in 1969, having learned nothing from the history of Leninist sabotage that Harrington warned about in Port Huron.

He won national renown during the very months that he sabotaged his reputation on the Left. To a much larger audience than joined SDS, Harrington was the author of The Other America, nearly always called “the book that launched the war on poverty.” In December 1958 Commentary editor Anatole Shub asked him for an article on poverty, notwithstanding that Harrington knew little about it. His many articles for Commonweal and Dissent never mentioned this issue, and his only reference to it occurred in a Commentary article on public housing. But Harrington was always a quick study, and Shub figured that his speaking tours and the Catholic Worker must have taught him something.

Harrington drew a vivid picture of the poverty existing alongside American prosperity, explaining it with an ill-considered version of a dubious concept. His article, “Our Fifty Million Poor,” explained that rich America had so much poverty because poverty creates a culture of its own that cuts across regional and national boundaries. Anthropologist Oscar Lewis contended that the poor of Mexico City, San Juan, and New York had more in common with each other in terms of interpersonal relations, family structure, time orientation, value systems, and spending patterns than with middle-class people of their own nations. Harrington agreed that the poor lived in a culture of poverty, though he employed this idea in a broad fashion that played down Lewis’s emphasis on cultural norms, replacing it with Harrington’s emphasis on economics and social policy. According to Harrington, the culture of poverty thwarted all piecemeal attempts to abolish poverty. America needed a comprehensive program dealing with housing, schools, medical care, labor rights, and communal institutions.

In a subsequent article he argued that the new poverty was more degrading than that of nineteenth-century immigrant communities because they were bound together by strong families, neighborliness, ethnic and religious bonds, and aspirations of a better life. The new “slums” were sites of broken families and anomic despair lacking any sustaining culture. Harrington said America needed housing programs that interspersed the poor among working class and middle-class communities. His articles appeared just as poverty emerged as a public issue, catalyzed by John Kennedy’s primary campaign in West Virginia. Publishers asked Harrington for a book, but he declined because Shachtman told him to concentrate on building the party. Economist Herman Roseman countered that Harrington had a moral duty to illumine a problem that economists ignored. Macmillan offered Harrington a $500 advance, a huge sum for an activist always pinched for bus fare.

The Other America said that fifty million poor Americans lived in a world invisible to middle-class Americans, existing mostly in rural isolation and crowded urban slums. They were unskilled workers,

migrant farm workers, the elderly, and oppressed racial minorities. Harrington argued that most Black Americans were poor because America’s society, economy, and unconscious were racist through and through. He described the situation of the American poor in two interchangeable ways: “The poor are caught in a vicious circle; or, the poor live in a culture of poverty.” In fact, these were not interchangeable conceptions. Lewis described the culture of poverty as a system of cultural values contrasting with middle-class values, which he said described perhaps one-fifth of the U.S. American poor. Harrington played down the idea that the poor subscribed to alternative norms, yet he heightened its stigma by describing all impoverished Americans as victims of the culture of poverty. To Harrington, the culture of poverty was a vicious circle, not a choice. The poor got sick more than others and stayed ill longer than others because they lived in unhealthy neighborhoods, ate bad food, and lacked decent medical care, which hurt them in the job market.

To Harrington, the culture of poverty was a vicious circle, not a choice.

Lewis disliked Harrington’s economic interpretation of the culture of poverty and took no interest in his policy proposals, believing that revolutionary socialism was the only cure for the culture of poverty, and thus for poverty. Harrington applied his newfound optimistic politics to the poverty issue. Only the government was big enough to finance a comprehensive national program. He wanted community organizers and other local agencies to organize the poor and coordinate anti-poverty programs funded by the government. Americans, he said, needed to be shamed by the facts and stirred to action.

The Other America was published in March 1962 and Penguin bought the paperback rights, which financed a year of getaway in Paris for Harrington. Dwight Macdonald emoted for 40 pages in the New Yorker about the book, making it required reading for social scientists, government officials, student activists, and intellectuals. Economic adviser Walter Heller gave a copy to Kennedy, who may have read it before ordering a federal war on poverty three days before his assassination. Meanwhile, Harrington had no idea the book was hot. Returning from France to New York in December 1963, he struggled to cope with media calls, stunned at becoming somebody that ABC News would call.

Lyndon Johnson, in his first State of the Union address, declared war on poverty, telling Heller that abolishing poverty was his kind of program. Congress passed the Economic Opportunity Act in August 1964, appropriating $800 million to fund the new Office of Economic Opportunity headed by Peace Corps director Sargent Shriver, who appointed Harrington to the organizing group. Shriver briefed him on the program’s mandate and budget, and Harrington objected that America could not abolish poverty by spending “nickels and dimes.” Shriver archly replied, “Oh really, Mr. Harrington. I don’t know about you, but this is the first time I’ve spent a billion dollars.” This was another favorite Harrington story, always told to illustrate that LBJ low-balled what it would take to wipe out structural poverty in America.

For a moment, Democratic realignment was very real. Johnson and the Democrats won a landslide victory in 1964 that seated 51 new Democrats in the House. Great Society legislation made 1965 the highlight year of every liberal Democratic politician’s career. AFL-CIO leader George Meany proclaimed that the moment had come to fulfill the promises of the New Deal, and Shachtmanites took high positions in the AFL-CIO. Agenda items left over from the dismal end of the Truman Administration barreled through Congress. A huge bill supporting elementary and secondary education passed in April 1965. Major legislation established Medicare and Medicaid, national endowments for the arts and humanities, new environmental standards, immigration reform, and a federally guaranteed right to vote.

IN the fall of 1965, Harrington attended a Texas-style buffet dinner in the White House to plan a conference on civil rights. Johnson welcomed the participants, and Mississippi civil rights leader Aaron Henry marveled to Harrington, “Mike, we’re eating barbecue in the White House.” To Harrington, that was the last gasp of the good feeling era. Johnson promised in 1964 not to escalate the war in Vietnam; then in February 1965 he massively escalated, bombing North Vietnam and instituting a military draft. Protests erupted immediately on campuses. SDS organized marathon all-night “teach-ins” to educate students about Vietnam and American foreign policy. The first big SDS antiwar demonstration took place on April 17, 1965. Twenty-five thousand protesters showed up in Washington DC for a demonstration that was mild and nice compared to its successors. No Vietcong flags were unfurled, no American flags were burned, no declarations of solidarity with Hanoi were issued, and civil rights anthems were not yet reprised in homage to Vietnamese Communist leader Ho Chi Minh. But the antiwar movement grew radical very fast.

Counterinsurgency failed and bombing North Vietnam merely strengthened the determination of the insurgents. Thomas embarked on a nationwide campus tour to plead for an antiwar movement that did not burn American flags or romanticize Vietnamese Communists. He implored students to cleanse the American flag, not burn it. Harrington put it more aggressively, protesting that ‘end the war’ quickly veered into pro-Communist rhetoric, a disaster for the antiwar movement. Pro-communism was not innocent, he warned, and apocalyptic ‘final conflict’ rhetoric would not remain mere performance. Minh’s mass-murdering collectivization of North Vietnam was an ugly preview of what a communist victory would look like in South Vietnam. Those who waved Vietcong flags made it harder to end the war.

New Left leaders were willing to hear such criticism from people they respected and felt respected by, such as Thomas and journalist I. F. Stone. They turned off Harrington, whose tiny generation barely existed on the Left. Basically, the Left was a thirties generation facing off against a sixties generation. Harrington bottled up his intense inner conflicts to the point that two of his closest friends, Irving Howe and Deborah Meier, didn’t know he had a nervous breakdown. They had to read about it in his memoir. On March 14, 1965 Harrington ended a California lecture tour by speaking about poverty at a Unitarian Universalist church in San Diego. He got his customary introduction, strode to the lectern, and nearly fell to the floor. It was the first flash of his breakdown, which he blamed on overwork. He assured himself while hustling to the Selma March that his health would improve.

Instead, his anxiety took hold of him, exploding at trivial intrusions, setting off profuse sweating and tremors in his chest, and turning streets into angled distortions, like the mirrors of a funhouse. Reluctantly Harrington accepted that he was not exhausted and had no physical ailment. This crisis came straight from his psyche, requiring four years of psychoanalysis to determine that he did not know how to be the minor celebrity who took calls from ABC, delivered $1,000 lectures, and should have been a father figure to the New Left. His disdain for middle class life had taken him to the Catholic Worker and then to Shachtmanite Marxism, a utopian vision of catastrophe yielding revolutionary change. Now he was some kind of middle-class Marxist, surely an absurdity—which set him on the path of proving otherwise. When Harrington married a Village Voice writer, Stephanie Gervis, in 1963, he vowed that marriage would not change him, only to learn that the nuclear family is bourgeois for a reason. In 1964 he earned $20,000, a mortifying sum to him. Harrington never grew comfortable with making a nice living off criticizing capitalism.

His disdain for middle-class life had taken him to the Catholic Worker and then to Shachtmanite Marxism. Now he was some kind of middle-class Marxist, surely an absurdity—which set him on the path of proving otherwise.

By 1966 he believed that a Communist victory was inevitable in Vietnam and it would be a lesser evil to expanding the war. Shachtman raged in refutation that Communism was the greater evil and the war was not lost. America had to keep fighting until the Communists were defeated. He said he was fine with “we want negotiations,” as long as the conditions were such that Minh would never agree. On that dubious ground the Shachtmanites founded a group in 1967 called Negotiations Now. It posed as a moderate alternative to SDS radicalism, giving Socialists and prominent liberals a foothold in the antiwar movement.

Harrington said he did not blame Americans for believing their nation is an exception to the European curse of ideology. Geographic location and expanse, the American Constitutional order, capitalist prosperity, and new technologies dashed the dreams of American Socialists. Americans are utopian pragmatists who believe that social problems are solved in the middle of the road. But Harrington stressed that realigning elections do occur. The elections of 1860, 1896, and 1932 were realigning. Johnson’s blowout victory of 1964 seemed, at first, to validate the Socialist dream of realignment, but the racial backlash elections of 1966 proved otherwise. Harrington was poorly positioned to protest that the Vietnam War destroyed Johnson’s Great Society, and he wanted very much not to believe that the civil rights movement triggered a realigned American politics in the wrong direction. In Toward a Democratic Left (1968), he said Johnson was failing because he didn’t put forth a new social vision. Johnson settled for half-versions of old policy goals, turning Truman’s call for universal health insurance into a Medicare program covering the elderly and some of the poor. Johnson-style liberalism, Harrington lamented, had no bold vision of a better America. It was merely what its New Left critics said, the Establishment.

THIS was the political context in which Harrington dropped the Marxian focus on working-class deliverance, contending that the key to a better politics was the rise of a “conscience constituency” he called “the New Class.” Sociologist David Bazelon, retrieving the “New Class” argument from its anarchist and post-Trotskyite history, said there was a great new mass of people who benefited from the economic prosperity of the 1950s, went to college, moved to the suburbs, and swung every recent election. The political identity of this new political force was not yet established. Perhaps it would use its newly minted degrees and professional class jobs to enrich itself, or perhaps it would ally with the poor to realign American politics in a progressive direction. Harrington bet on the latter possibility. Blue-collar workers were a minority of the labor force, white-collar work was expanding dramatically, and the meaning of the middle-class category was changing. Harrington argued that technological change was creating voters never imagined in Marxian theory.

He took a page from the Port Huron Statement, contending that the university was the site of the next progressive upsurge. The growing core of the New Class was university educated and worked in the public sphere—scientists, technicians, teachers, policy experts, and consultants. It gained social leverage through position and the use of its special expertise, not by making money. Harrington said the New Class was predisposed by its education and work experience to economic planning. Admittedly, the rush to graduate education reinforced some of the worst competitive instincts in American life; middle-class parents obsessed about getting their kids into Harvard. But education, Harrington reasoned, is distinctly broadening and subversive. Like it or not, the New Class was growing and increasingly powerful. What kind of values would the newly educated take into their careers as scientists, professionals, and social planners? Harrington said everything was at stake in this question. The New Class might become an ally of the poor and the unions, or “their sophisticated enemy.”

Toward a Democratic Left, though geared to the 1968 campaign, applied to a later moment, not its own. It was an argument for precisely the “conscience constituency” that won the Democratic presidential nomination for George McGovern in 1972. Harrington refashioned his role on the Left by heralding the vision of a new progressive politics. It had room for people like himself who held a muddled position on Vietnam and respected the sensibilities of regular Democrats. But America exploded in 1968, shattering what might have been. King and Robert Kennedy were assassinated, Democrats nominated Hubert Humphrey, the winner of zero primaries, and Richard Nixon won the White House with a shrewd appeal to white resentment and fear. Thomas faded in the summer of 1968 and Harrington was elected as party chair. For ten years, he had been useful to the Shachtmanites as they strove for majority control of the national committee. In July 1968 they won a majority and no longer needed Harrington. His influence in the party plummeted just as he became party chair.

The Shachtmanites clung to the AFL-CIO hierarchy, the Socialist Party’s antiwar leftwing resigned in disgust, and Harrington tried to hold the party together, standing for muddled unity. It took him until January 1970 to call America to leave Vietnam, catching up to 40 percent of the public. If Socialists had to be with the labor movement, and it was a stronghold of Cold War militarism, he was stuck, for too long. His friends left the party and the Shachtmanites responded by throwing off their pretense that they held some kind of antiwar position; Communism had to be defeated in Vietnam. Harrington countered that the U.S. was not obligated to wage anti-Communist wars wherever Communism advanced. The lesser evil was to get out of Vietnam and accept a Communist victory. This position so enraged Shachtman that he never spoke again to Harrington.

Now the fight was on for the soul of the Socialist Party. Tom Kahn, Penn Kemble, Rachelle Horowitz, Bayard Rustin, Al Shanker, Arnold Beichman, Paul Feldman, Carl Gershman, Sidney Hook, Emanuel Muravchik, and Arch Puddington led the Shachtmanite faction, which renamed itself the “Majority Tendency” caucus. Harrington tried to rally his allies, begging them, one by one, to return to the party. He got some blistering replies. The struggle for the Socialist Party mapped onto the 1972 Democratic presidential campaign. The Shachtmanites supported Cold War stalwart Henry Jackson until he dropped out; then they switched to Humphrey. McGovern won the nomination by advocating withdrawal from Vietnam and amnesty for draft evaders. To the Shachtmanites he was a catastrophe—preachy, idealistic, feminized, and anti-interventionist. It did not matter that McGovern was the most pro-union nominee in the history of the Democratic Party. He epitomized the kind of liberalism that came out of the 1960s, which they loathed.

The AFL-CIO voted 27 to 3 to take no position on Nixon versus McGovern. The UAW, AFSCME, Machinists, and Communications Workers endorsed McGovern on their own, but losing the AFL-CIO hurt the Democrats badly. Formally, the Socialist Party “endorsed” McGovern in the same disingenuous way it previously “endorsed” the antiwar movement—by showering him with insults and faint praise. A National Committee meeting of October 1972 was the last straw for Harrington. He resigned as chair, protesting that most of the Shachtmanites were pro-Nixon. The following month they rejoiced when Nixon crushed McGovern; a month later, they renamed the party Social Democrats USA. The Shachtmanites had come from tiny sectarian nowhere to capture the Socialist Party and scale the ranks of the labor movement. They relied on funding from their historic enemy, the Old Guard textile unions, until they reached the apex of the AFL-CIO. Then they co-founded the most consequential political-intellectual movement of the late twentieth century, “neoconservatism,” the name that Harrington hung on them in September 1973 as an act of dissociation.

The mission of the original neocons was to retake the Democratic Party from McGovern liberals. Two groups came together to try it. One consisted of the Shachtmanites, and the second consisted of intellectuals from the Humphrey and Jackson camps, especially Public Interest editors Daniel Bell and Irving Kristol, Commentary editor Norman Podhoretz, and sociologist Daniel Patrick Moynihan, plus Midge Decter, Nathan Glazer, Max Kampelman, Jeane Kirkpatrick, Richard Perle, John Roche, Ben Wattenberg, and Paul Wolfowitz. These two groups melded together in a classic Leninist vehicle that Kahn founded with AFL-CIO money, the Coalition for a Democratic Majority. Harrington’s label for them stuck because it named the rush of Shachtmanites and Jackson liberals to the political Right.

Neocons rang the alarm that America was losing the struggle for the world. They claimed the Soviet Union was preparing to fight and win a nuclear war against a cowardly America that feared the Soviet Union too much to resist it. Henry Kissinger, they claimed, imperiled the nation as Secretary of State under Nixon and Gerald Ford, capitulating to the Soviet enemy. This contention propelled the neocons to bond with a Republican upcomer who shared their view of the crisis, Ronald Reagan.

In the mid-1970s, Harrington’s new group, DSOC, out-competed the neocons for influence in the Democratic Party. Then he watched the neocons go on to spectacular success in the Republican Party. Neoconservatism was the last phase of the Old Left and a cry of revulsion against the antiwar, Black Power, and feminist movements. Harrington never lost his appalled fascination that his former comrades swept into power by providing ideological ballast for Reagan. The world changed profoundly, he said, in the mid-1970s. The prosperity boom of the post-World War II era ran out and the democratic socialist tack of bonding with liberals to defend the welfare state paid diminishing returns. It was time to rethink the Social Democratic socialism that had settled too readily for the welfare state. Harrington spent his remaining years, until 1989, doing so with exemplary passion, a Catholic atheist who bore the burdens of democratic socialist leadership and wore the mantle of a secular prophet.

Gary Dorrien is the Reinhold Niebuhr Professor of Social Ethics at Union Theological Seminary and Professor of Religion at Columbia University. His many books include most recently Social Democracy in the Making: Political and Religious Roots of European Socialism (Yale University Press, 2019) and In a Post-Hegelian Spirit: Philosophical Theology as Idealistic Discontent (Baylor University Press, 2020). He is also a member of the ICS Advisory Board.