Art can be prophetic under capitalism only if it emerges from an explicitly anti-capitalist orientation. To rightfully critique capitalism, art must arise from outside its grasp. This was what I learned when I listened to the collaborative rap album Kolateral (“Collateral”), created by Filipino hip-hop artists disillusioned with both the cultural and political establishments. In the wake of former president Rodrigo Duterte’s fascist “War on Drugs,” which claimed the lives of over 30,000 urban poor, many artists recognized that mainstream platforms—concert halls, brand deals, and pop radio—would not be the sites for genuine critique. Instead, they have turned to the streets and activist spaces to voice the dissent mainstream artists and producers refused to hold.

Interspersed with audio clips of gunfire and the mourning of Drug War victims, Kolateral’s lyrics documented the lives shattered by Duterte’s fascism and urged listeners to confront the social conditions that enabled his rise—chief among them the widespread poverty imposed by capitalism and the tightening grip of fascism on the Philippine economy. The album’s closing track, “Sandata,” distills its message into a defiant refrain: “Pasistang rehimen, buwagin!” (Bring down the fascist regime!)

Kolateral has proven to be a “timeless” work of protest art—indeed, prophetic art—precisely because it refused to play by the rules of capitalism or Duterte’s fascism. A similar spirit animates Walang Panginoon ang Lupa (The Land Has No Lord), a collaborative album by the artist-peasant collective Artista ng Rebolusyong Pangkultura (Artists of the Cultural Revolution). Written toward the end of Duterte’s administration, the album features the fusing of hip-hop, hardcore electronic, and punk tracks created by marginalized artists to expose the “rotting system” of exploitation, capitalist violence, and land dispossession plaguing rural communities. As the title declares, the land has no lord—it must not be lorded over by capitalists or those who seek to ravage the earth for profit.

Unlike much of the music produced and circulated to enrich the capitalist class, the creators of Kolateral and Walang Panginoon ang Lupa made music to confront, to challenge, and to resist. In doing so, they issued a call not for profit, but for structural change and social renewal. And this is the key: their work is prophetic precisely because it emerges from a different moral orientation than the music crafted to extend capitalism’s reach. It is their explicitly anti-capitalist posture that gives their art its prophetic edge—shaping its power as protest and its radical musicality.

In his work Art and Moral Change, theological ethicist Ki Joo Choi argues that art, in and of itself, is not sufficient to generate ethical transformation. One cannot simply take their child to a museum and expect that, by looking at “good” art, the child will emerge as a more moral person; aesthetic encounter alone does not constitute moral formation. Choi instead contends that art does not change the world on its own, for ethics must precede aesthetics. The ends toward which we create and deploy art must be defined from the outset. In short, art must be oriented toward a moral vision. In the Philippines, a similar conversation unfolded within the underground music scene, which led to the emergence of hip-hop albums like Kolateral and Walang Panginoon ang Lupa as forms of prophetic refusal.

The history of hip-hop as a genre can be traced to gentrified, marginalized, and segregated Black spaces. It became a mode of resistance, a genre of the dispossessed. As religious scholar Imani Perry puts it, hip-hop artists emerged as “prophets of the hood.” This is true of artists such as Noname, Tupac Shakur, Lauryn Hill, and others. Hip-hop was prophetic precisely because it interrogated and challenged a racial capitalist social order—because it came from struggle, not stardom.

Yet over the decades, hip-hop has grown into one of the most dominant and profitable genres in the American music industry, raising the question of whether it still maintains its prophetic modality. If hip-hop is now firmly housed within the very capitalist structures it once critiqued, can its condemnations of capitalism still carry integrity or weight?

This is precisely why artists such as Kendrick Lamar—despite the incisiveness and power of his lyricism—cannot be considered sufficiently prophetic on his own. As a member of the capitalist class, with a net worth of over $140 million, the wealth his art generates compromises the moral integrity of his message. However compelling his critiques of anti-Blackness and the police state are, they remain entangled with the very system his music seeks to confront. If we are to seek the truly prophetic, we must therefore look beyond Kendrick to the masses who carry his words into the streets—shouting “We gon’ be alright” as the police state presses down upon them. Prophecy emerges not from the house of capitalism but from the trenches, in voices that rise not for profit but from what theologian Colton Bernasol describes as the conditions of everyday struggle: “the long-term nature of fighting for change.”

Filipina thinker Neferti X. M. Tadiar calls such voices “remaindered life”—those who exist outside the house of capitalism because they have been cast out, exploited, and rendered disposable by it. They struggle, survive, and make life possible even in the peripheries of empire. And it is from these thresholds that prophetic art most often emerges: not polished for mass appeal, but sharpened by necessity, grief, and resistance.

This is the very ground from which Kolateral and Walang Panginoon ang Lupa arise—from communities forged in the crucible of exploitation and resistance. The albums’ creators make hip-hop to disrupt the logics of the music industry in pursuit of a better world. These works do not merely reflect suffering; they confront the systems that produce it. They are prophetic precisely because they speak from below—with clarity, urgency, and a moral vision born of struggle. In them, art becomes more than expression; it becomes a form of refusal—that is, the refusal to settle with the world that empire created.

In a world where even capitalism’s critics are commodified, the task is to elevate voices and discern where they are speaking from—and what they are calling us toward. As the Apostle Paul claims, “not all things are beneficial… not all things build up” (1 Cor. 10:23). Indeed, not all art is beneficial, and not all art builds up.

Only prophetic art does—art that moves with the quiet revolutions stirring in places deemed disposable and left behind. So we must ask: which art, and whose, is building up the liberated world we struggle for? Prophetic art will not promise comfort, success, or spectacle. It will demand something more of us. It will ask for solidarity, imagination—risk. It will insist that we both listen and respond.

And if we are to take seriously the ethical imperative that Choi and Tadiar describe, then we must attune our ears not to what is profitable or popular, but to what rises from the underbelly of capitalism, bearing witness to another world still struggling to be born.

Yanan Rahim N. Melo (he/him) is a journalist from the Philippines who covers religion, politics, and immigration.

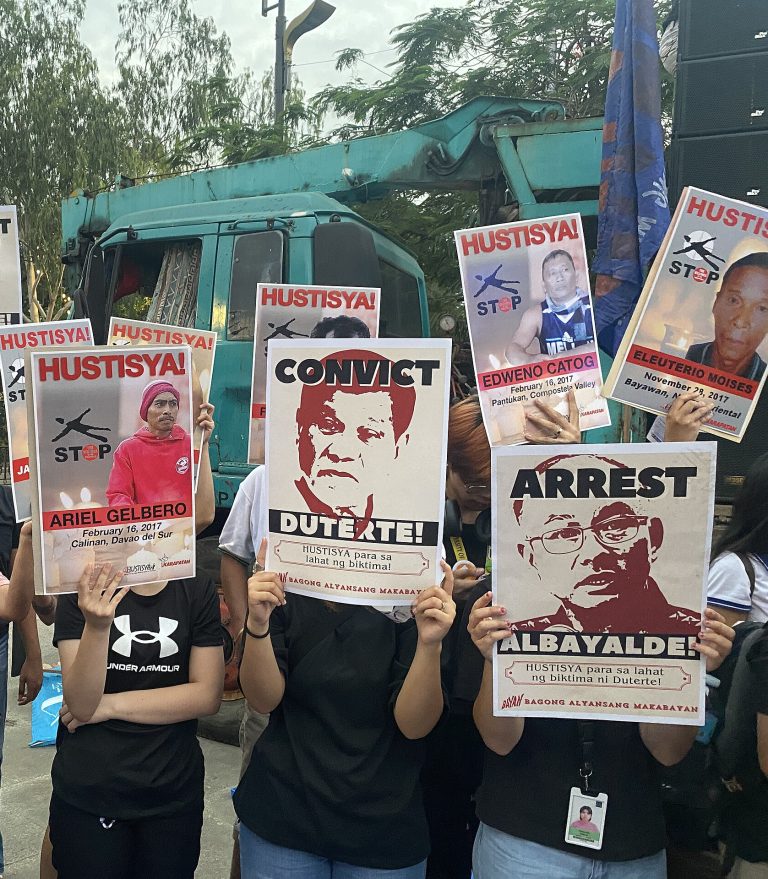

Image Credit: Kej Andrés (Ryomaandres), “Rally for justice for EJK victims on Duterte’s birthday, March 28, 2025,” licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, Wikicommons.