One of the major challenges of being a Christian socialist in twenty-first-century America is finding resources for resistance. Material resources are essential, of course, but so too are sources of intellectual and spiritual insight. Philosopher Elizabeth Anderson, in her recent book Hijacked: How Neoliberalism Turned the Work Ethic Against Workers and How Workers Can Take It Back, stresses the need to reassemble a canon of social democratic and socialist thinkers who can guide us toward a more just economy. This need is even more urgent for the American left generally, and Christian socialists especially, as they confront the idolatries of a religious right that elevates Christendom and Mammon above all else.

One historian and activist who deserves renewed attention is R. H. Tawney. Although he exerted immense influence on early twentieth-century British politics, Tawney virtually disappeared from public conversation for decades after his death in 1962. Fortunately, theologians such as Gary Dorrien and historians such as Madoc Cairns have brought him back into contemporary dialogue. In Social Democracy in the Making, Dorrien commends Tawney’s “chaotic brilliance” and earnest defense of equality in a class-divided Britain. In Jacobin, Cairns describes Tawney as a “diligent and innovative historian, an insightful critic of liberalism, and an articulate, relentless defender of socialism as freedom.” And in his concise guide Socialism, author Peter Lamb applauds Tawney as the most powerful exponent of Christian “ethical” socialism to emerge in the United Kingdom.

Here, I make the case for what Tawney still has to offer Christian socialists today. Most notably, he shows how socialism need not be a bloodless, mechanical philosophy centered on class analysis and long digressions on the law of value. All of that is important, of course, but Tawney showcased a different side of the great socialist tradition: one that is ethical, practical, and down to earth. If, as philosopher Antonio Gramsci urged, we need much Marxist pessimism of the intellect, Tawney reminds us we also need warmth of the soul.

To understand why Tawney matters, it helps to begin with his life. At first glance, he may have seemed an unlikely champion of the working classes. Born into a well-off family in Calcutta in 1880, raised by his father who was a Sanskrit scholar with high academic expectations, and educated at Oxford, he might easily have settled into the establishment. Yet Dorrien chronicles Tawney’s struggles to fit into the upper crust since he lacked the “outgoing confidence of his peers.” He also struggled academically, to the great disappointment of his father. And so, rather than cruising to a well-heeled appointment, Tawney took a job teaching theology and literature at Toynbee Hall, a settlement house serving London’s poor. Exposed to the realities of working-class life, he had his convictions on class struggles reshaped. He joined the executive board of the Workingmen’s Educational Association, beginning a lifelong career integrating intellectual ideas and pedagogy with socialist political activism.

Compelled by his work at Toynbee Hall, Tawney enlisted in the First World War, driven by guilt that younger, poorer men were being drafted. Experience on the front lines deepened both his faith and his conviction that a better world needed to arise from the ashes. He returned to Britain with new confidence, joining the then socialist Labour Party in 1918, where he remained a member for life. Between 1920 and 1931, he published his most influential works: The Acquisitive Society (1920), Religion and the Rise of Capitalism (1926), and Equality (1931). These books form a thematic trilogy, which together accounts for the rise of acquisitive capitalism, critiques its moral failures through a Christian lens, and presents a program for a better kind of society.

After Clement Attlee’s sweeping Labour victory as prime minister in 1945, Tawney became widely recognized as one of Labour’s chief intellectual influences. His earlier works had already shaped the party’s moral imagination, but the triumph of the welfare state vindicated many of his convictions. Even his later writings, including the posthumously published The Radical Tradition: Twelve Essays on Politics, Education and Literature (1964), demonstrated a mature intellectual full of confidence that his core arguments had been borne out in practice. This was the heyday of the British welfare state, and Tawney threw himself into intra-Labour debates about what direction the party and movement should turn, anchoring it to a vision of social democracy. Yet this very role also contributed to his reputation on the far left as too much of an establishment figure. Even those who saw him as a luminary like a young Alasdair MacIntyre criticized him for a lack of revolutionary ambition. Tawney died in 1962, at age eighty-one, at the end of a life neither seamless nor uncontroversial, but undeniably successful in shaping the democratic left.

Tawney’s most enduring work, Religion and the Rise of Capitalism, stands as a classic work of critical history and social theory that compares favorably to Max Weber’s The Protestant Work Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Where Weber traced how Protestantism fostered capitalism, Tawney offered a more nuanced reading: Protestant traditions contained both proto-socialist and capitalist impulses. Condemning Protestant theology and spirituality wholesale as capitalism’s handmaiden, he argued, was reductive. Looking at his native England, Tawney observed how many early Protestant sects committed themselves to a far more proto-socialist ethic. He wrote that in “every human soul there is a socialist and an individualist, an authoritarian and a fanatic for liberty.” For example, Puritans contained an “element which was conservative and traditionalist, and an element which was revolutionary; a collectivist which grasped at an iron discipline, and an individualism which spurned the savourless mess of human ordinances; a sober prudence which would garner the fruits of this world, and a divine recklessness which would make all things anew.” Puritans also often renounced acquisitive ethics by stressing the importance of community and fairness in consumption and exchange. They praised the moral situation of the working classes and condemned the idle aristocratic rich for living off the hard work of others, distilled in their biting motto, “You work; I eat.” Besides the Puritans, Protestant sects like the Quakers and Levellers argued for Poor Law reforms and stressed the importance of Christian social obligations and humility. These groups envisioned a faith grounded in communal justice, mutual aid, and moral equality before God.

But alongside these traditions ran a very different Protestant ethic, one that emphasized “individual responsibility, not social obligation,” viewing aid to the poor as indulging idleness and commending moral weakness. This emerging outlook sanctified self-reliance and worldly success, laying the groundwork for a more proto-capitalist individualism. Tawney’s most profound ruminations are on this branching strain. He saw how the “virtues of enterprise, diligence and thrift”—valuable in themselves—were invested with “super-natural sanction, [turning] them from an unsocial eccentricity into a habit and a religion.” Capitalists and their cheerleaders turned business into a battlefield where individual character supposedly triumphed, even as structural privilege determined outcomes. Furthermore, the wealthy convinced themselves they owed society nothing. As Tawney observed:

Few tricks of the unsophisticated intellect are more curious than the naïve psychology of the business man, who ascribes his achievements to his own unaided efforts, in bland unconsciousness of a social order without whose continuous support and vigilant protection he would be as a lamb bleating in the desert.

These ideological and psychological foundations, he argued, underwrote what Tawney memorably called the “acquisitive society”: a social order emphasizing rights over duties, property without obligation, and wealth without service. In such a society, hyper-individualism becomes the norm. Although Tawney himself was not opposed to basic liberties and indeed fought vigorously for them, his sharpest criticisms targeted the selfish acquisitiveness induced by capitalist society, particularly the notion that one has a right to immense volumes of property even when it could serve the needs of the destitute. This ideology moralized inequality. The wealthy appeared virtuous and industrious; inversely, the poor were portrayed as lazy, shiftless, and so deserving of their lot.

If the ethical basis of society suggested that wealth came from hard work, thrift, and good character, then poverty must be read as evidence of vice. Tawney, though, dismantled this logic as a clear falsehood:

For property which can be regarded as a condition of the performance of a function, like the tools of the craftsmen, or the holding of the peasant, or the personal possessions which contribute to a life of health and efficiency, forms an insignificant proportion, as far as its value is concerned, of the property rights existing at present…The greater part of modern property has been attenuated to a pecuniary lien or bond on which the product of industry which carries with it a right to payment, but which is normally valued precisely because it relieves the owner from any obligation to perform a positive or constructive function.

In other words, the very structure of capitalist property undermines the claim that wealth corresponds to hard work. Tawney anticipated the hypocrisy that we still see today. This “work ethic” argument is endlessly invoked by professional cheerleaders of extreme, overindulgent wealth, from politicians passing tax breaks for the ultra-wealthy to celebrity intellectuals like Ben Shapiro. Yet, if taken seriously, the capitalist ethic would indict capitalism itself. After all, the most vital labor in our modern society is performed by those who earn the least, given the least, and receive the least respect: migrant farmers, grocery clerks, nurses, delivery drivers. Meanwhile, many who inherit privilege or speculate for profit remain convinced it would be a criminal injustice to tax their capital gains to fund basic healthcare for all.

From diagnosis, Tawney turned to prescription in The Acquisitive Society, outlining what a just and functional alternative to the acquisitive society might look like—namely, a socialist society. Earnings ought to be tied to function–rewards proportional to contribution–so that those who labor most directly for the common good enjoy more of the good things of life. In Equality, he further compiled statistical evidence to support growth and “communal provision” of basic goods, especially quality education for the poor. Later, in his essay “British Socialism Today,” he recommended experimenting with various forms of public ownership and industrial democracy in which workers would have real say in the governance of their workplaces. Beyond abstract musings, Tawney’s arguments were taken seriously by a Labour party still animated by socialist ideals before drifting rightward under pro-market leaders like Tony Blair and Keir Starmer.

Tawney’s vision was not without its flaws. Softly nationalistic, he lacked a deep awareness of the moral failures of British imperialism. Additionally, his work carried no sensitivity to issues of race and gender, and he gave little thought to the ways that women are oppressed by systemic forms of patriarchy or the way that capitalism depended on their unpaid socially reproductive labor. A society that rewarded its members based on function, as he proposed, would owe women an enormous unpaid debt. Conceptually, Tawney remained tethered to the moral universe established by Protestantism, especially its work ethic. He inverted its moral charge by insisting that laborers, not capitalists, embodied true diligence, but he did little to question the framework itself and thus limited the scope of his arguments. Later socialists like G. A. Cohen might have noted that by simply inverting the moral valence, Tawney still implied that hard work should be the basis of reward. A socialism that seeks to care for the sick, elderly, and disabled must move beyond that premise. John Rawls was right to argue that a just society ensures the well-being of its least advantaged members, regardless of their contributions to its functioning. In today’s landscape of entrenched meritocratic mythologies that justify wealth by suggesting the yacht class “worked hard,” socialists would be wise not merely to invert the moral hierarchy but to change the framework altogether.

Nevertheless, Tawney stands out as one of the most admirable and thoughtful representatives of Christian ethical socialism at its most enterprising. His example still has much to teach the contemporary left. He embodied qualities that made him both an effective reformer and moral visionary. Uniting intellectual rigor, worldly engagement and spiritual depth, his life and work offer a model of what socialism can be.

Tawney’s socialism was decidedly grounded and practical. He maintained deep connections with the British working class and the political establishment, and at his best, he integrated these diverse experiences with an uncommon good sense. Reading Equality, one is struck by how straightforward his moral vision was, whether in arguing for reforms to ensure equal education for all, or in stressing that a wealthy nation like the United Kingdom has no excuse for leaving its citizens poor. He wrote clearly and forcefully, showing that socialist thought need not be abstract or utopian but could speak plainly and penetrate everyday life. His prose is well suited to a political philosophy that not only seeks and expects power, but also knows what it will do with it once attained.

Tawney spoke beyond intellectual thought pieces and practical policies. He also reached into the spiritual dimensions of life, a realm too many modern socialists avoid or fear. He had a keen sensitivity to and affinity for what Freud disparagingly called the “oceanic” feelings of religious experience, and he was unapologetically filled with a fierce moral fire for justice that would better life according to the ethical demands of the Gospel. This kind of language is also one the left needs to recapture. It is no coincidence that in the United States, the left has been at its most successful under standout leaders like Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King, Jr., who combined a resolute practicality with precisely this visionary ethical seriousness. Make no mistake: this is a challenging register to hit. But it is one we need to get better at achieving.

It is precisely this fusion of the practical and the visionary that makes Tawney so relevant today. A common criticism from the right—and often from skeptics more broadly—is that socialism is too intellectualized, too disconnected from ordinary realities, and too lacking in spiritual imagination. Tawney’s example dismantles that perception. He showed that one can be both politically astute and spiritually alive. In doing so, he offered a model for Christian socialists and a template for the left more generally.

Indeed, these two elements of Tawney’s work—his practical reason and spiritual seriousness—belong together in a way any Christian socialist should recognize. The right has long monopolized the language of religious transcendence while tying it to low ethical ideals. Christian socialism, by contrast, seeks the realization of faith through the pursuit of actual justice. That is a task at once grounded and soaring.

Matt McManus is an Assistant Professor at Spelman College and the author of The Rise of Postmodern Conservatism and The Political Theory of Liberal Socialism amongst other books.

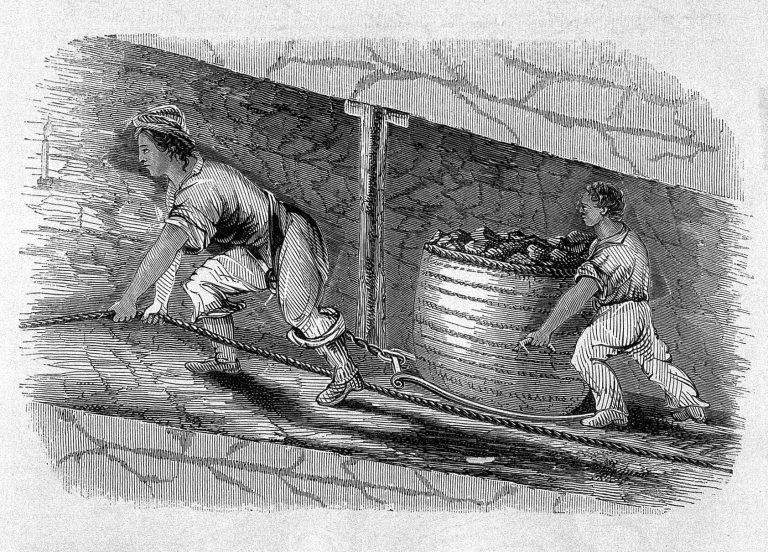

Image Credit: The physical and moral condition of the children. Wellcome Collection. Source: Wellcome Collection.